I rarely travel by plane but, when I do, I can’t help checking that little screen of bad LEDs at least five times an hour, to see the map of locations miles below. Many of them I’ve never heard of, and most of them I’ll never see. Their names appear on the screen like as many alchemic ingredients: Athens, Yerevan, Khartoum, Alexandria, Benares, Beijing, Kyoto, Karachi… As a child, I grew up behind the Iron Curtain in Czechoslovakia, thinking all of them out of reach. Then, in 1989, the curtain fell, the traveling costs sunk in the early 2000s, and my working wages rose above living minimum, leaving me enough money for travel. The whole world suddenly seemed to hold in my palm, and my geographic fantasies turned into reality. Space, once striated by murderous borders and financial impossibilities, became fluid. A teenage fascination for manga, zen and minimalist design were now all I needed to board a Shinkansen in Tokyo. On my way back from Japan, looking through the porthole at the vast plains of Mongolia, I got it into my head to discover them on horseback: I landed in Ulan Bator a few years later. I even considered going there by Transiberian from St. Petersburg.

This, of course, was deemed to change. If you really think of it, it did so as soon as 2001 and 2003, as the illegal (i.e. unsanctioned by the UN) occupation of Afghanistan and then Iraq by US armies set a stupid precedent, the consequences of which we are now paying, with a quarter of a century delay. Yet, however much we protested back then, marching in capitals with banners, insulting George W. Bush on the nascent social networks, the Middle East remained a distant abstraction, a desolate zone of dead-end wars that was all too easy to bypass, even in our dreams of Asia, through the immense territory of the Russian Federation. Looking back at the world I shared with many Western contemporaries in the early 2000s, I feel like staring in the disquieting mirror of Stefan Zweig’s World of Yesterday:

Thanks to the telephone, a human could already speak to another human in the distance, drive over in a horseless carriage at new speeds, even fly over, soaring up into the air in the fulfilled dream of Icarus. … They believed as little in barbaric relapses, such as wars between the peoples of Europe, as they did in witches and ghosts. … They honestly believed that the boundaries of divergences between nations and faiths would gradually melt away into a common humanity and that peace and security, these highest goods, would be shared by all mankind.

Stefan Zweig, 1942, Die Welt von Gestern. [author’s translation]

(Ohio State University Archives)

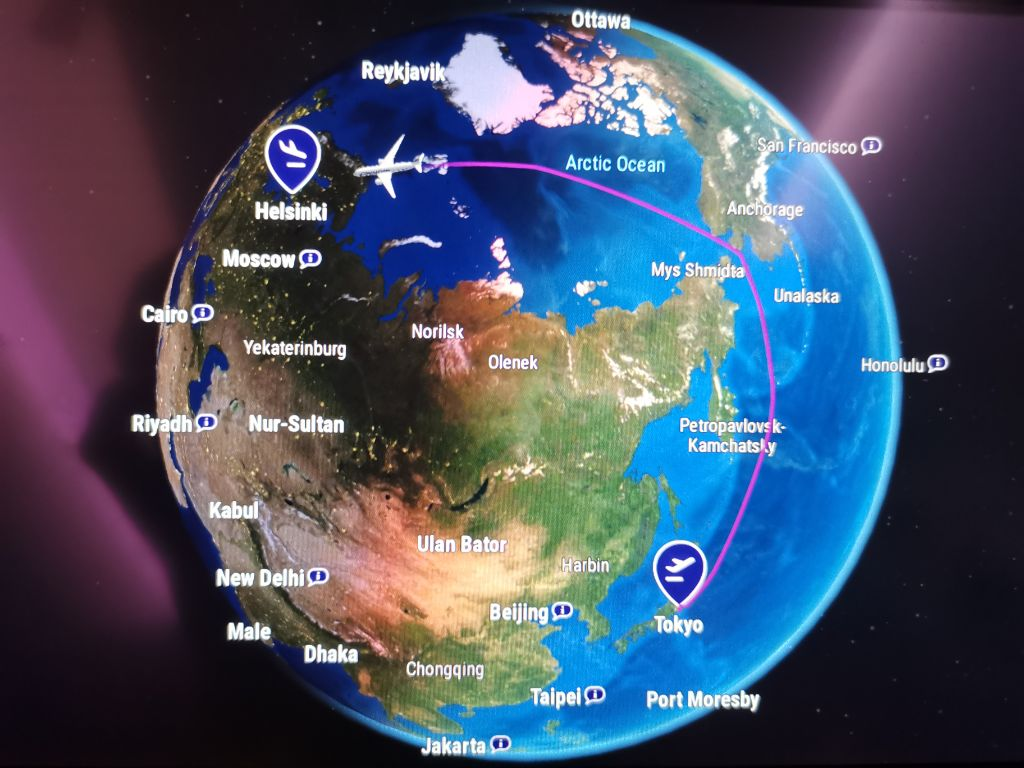

Twenty years later, a good friend of mine sent me a picture of his absurd route from Tokyo to Helsinki, starting not westwards as sound, but eastwards, south of Kamchatka, then through the Bering Strait all the way to the North Pole, and then back south to Scandinavia across the Arctic Ocean. Over six thousand such flights between Europe and Japan took place in the sole year of 2023. This means repeating, sixteen times a day, the feat of the navigator Richard Byrd and pilot Floyd Bennett. The men claimed to have flown over the pole in a Fokker F.VII aircraft on May 9, 1926, three days before Roald Amundsen, Lincoln Ellsworth and Umberto Nobile in a similar machine. Even a contemporary Airbus 359 still has to propel itself against the polar easterlies, through sharp temperature gradients, through the savagely overlapping warm and cold air masses, and through magnetic anomalies. Above all, the Tokyo-Helsinki trip via the pole amounts to 10’200 km instead of 7400 km, which implies at least 30’000 extra liters of fuel per trip. In other words, if we consider civil airline routes between Japan and Europe only, our dealings with Putin have already led us to burn seventy Olympic swimming pools full of kerosene. Ever since Crimea in 2014, and the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 over eastern Ukraine by Donbas separatists, things have only gotten worse. In May 2021, the Belarusian army forced a Ryanair Boeing 737, flying from Athens to Vilnius, to land in Minsk, so that Lukashenka could capture his political opponent Raman Pratasevich and have him tortured for six months. And then came the wars.

Photo by Daniel Maszkowicz.

On my way from Zurich to New Delhi in February 2023, we didn’t take the shortest route, either, but headed for Bucharest. The airplane’s wings slanted to the right shortly after we passed the Romanian shoreline; our route inflected southwards in the Black Sea. But why so far south? Why all the way to the Turkish city of Zonguldak? Sitting in my economy seat, I imagined the sky guide’s fear from wayward missiles fired by the Russian fleet. How ill-fated would it have felt, wouldn’t it, to get hit by a projectile destined to the civil populations of Kherson and Odessa! How unjust, even, to my Indian fellow flyers! Didn’t their government restrain from opposing the Russian invasion of Ukraine in the UN General assembly vote on March 2, 2022? Didn’t Modi keep smiling and shaking hands with Putin ever since?

We all carried on unharmed, but the ground truth was far more discomforting. Upon my return home, I checked on Google Earth, and realized that our pilot also sought to avoid Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan. An itchy reminder of the fact that one fifth of the Georgian territory is still under Russian occupation, and that, only months ago, Azerbaijani troops poured into Nagorno-Karabach, motivated by nationalistic revenge and Islamist bigotry, galvanized by Recep Tayyip Erdogan in the name of his pan-Turkic ambitions. Ceasefire talks were ongoing as our flight dodged the region in a large southern ark.

Conversely, flying over Iran posed no issue to a Swiss aircraft in February 2024. With a mixed feeling of fascination and dread, I took a photograph of the lights of Teheran glowing in the night. I remembered the few Iranian friends I have, all of them PhDs in architecture, social science or engineering. All of them smart, handsome and witty, and exceptionally resilient in adversity. If I go by their words alone, I imagine Teheran as a place of intense personal relations, infused by profound reflexivity, political consciousness, deep-rooted millennial culture, and that art of silence! oh! that precious art of communicating with the eyes, measured gestures and a few, carefully chosen words! This is an art that people take to exceptional heights in repressive regimes. In the worst conditions, it also encompasses the art of recounting terrible events with a noble and self-respecting sense of emotional measure. By myself, though, regarding horror, I fail to think of Iran without seeing ropes tightened around the necks of poets, without feeling the weight and the convulsion of muscles of the living bodies of artists and activists, lifted by cranes, for them to suffocate in minutes of excruciating pain above the satisfied grins of Shia revolutionary guards.

From Teheran, we progressed further south, and only turned eastward shortly before the city of Kerman, to avoid Afghanistan. Obviously, Taliban are not to be trusted, though I doubt any of them would risk unnecessary diplomatic attention by firing a surface-to-air missile at a Swiss aircraft. Why would they? After all, the Swiss Secretariat for Migration hesitates with the refugee admission of every single Afghan woman, and often denies it, even if she worked for a Swiss governmental agency prior to the Taliban takeover. The fact is, the new masters of Kaboul know by heart every misogynistic tafsir of the surahs, but cannot manage civil aviation. Their airspace lacks reliable air traffic control and is prone to collisions.

Only two months later, the situation changed dramatically. My friend took a similar route by the end of April, on his return journey from Eastern Asia with a stopover in Dubai. By April 13th, the Iranian army had fired no less than 120 ballistic missiles, thirty cruise missiles and 170 drones at Israel, in retaliation of the Israeli bombing of the Iranian consulate in Damascus. Nine of the missiles actually hit a target, and none made victims. Many of us thought, “Well, despite my total lack of sympathy for the Mullahs, I would struggle to argue that any country should stay arms crossed with its consulate bombed by a foreign power.” This wasn’t, of course, how Netanyahu’s genocidal far right regime saw it, and the World was holding its breath in expectation of Tsahal’s escalation. For civil aviation, all airspace between the Mediterranean Sea and the Hindu Kush had become unsafe, as revealed by the flight route recorded by my friend. The airline already took a considerable risk by heading directly from the Strait of Hormuz to the Caspian Sea.

They could have flown my friend south over Oman, instead, all the way around violence-torn Yemen and Somalia, and then east, over Kenya, Uganda, and Congo, then north-north-east, again, over the Central African Republic and Chad, thereafter bypassing the civil war zone in Libya, over Niger and Algeria. Avoiding this twice-as-long route was reason enough, it seems, for the airline company to take its chances. I guess most of the passengers felt the same.

Because a brief look at the global airspace shows what our world has become: an obscene gathering of kerosene-hungry, hyperactive fireflies from Northern America, Europe and East Asia. Busy, waiting in line, struggling to squeeze ourselves through corridors of safety in a war-torn space that resists our existential hunger, escapes from the grips of our best intentions and our governments’ power; unwilling, unable to question our ways of life, and to engage in a serious conversation about our common future with a Word that mostly loathes us, for reasons both corrupt and honestly legitimate, both thick as straw and soundly logical. We spend a considerable amount of our time trying to forget about the ground realities of explosions, deaths, rape, hunger and sickness, by taking refuge in abstraction, geometrical games, twisting geodesic arcs kilometers high in the troposphere.

As I write these lines, the armies of Russia, Israel, and many others spare no effort to jam GPS location systems, deeply impacting the safety of air travel.

Around 1922 in Paris, three thinkers, the French mathematician Édouard le Roy, the Russian geochemist Vladimir Vernadsky and the French theologian and paleontologist Teilhard de Chardin discussed and popularized the “noosphere“, a philosophical concept that refers to the layer of human thought and mental activity surrounding the Earth. The noosphere doesn’t have to rely on a material substrate but also encompasses the immaterial realm of thoughts and spoken language. In 1982, science fiction author William Gibson introduced the less generous concept of “cyberspace” in his short story Burning Chrome. Cyberspace is a noosphere limited to the realm of abstract steering mechanisms, whose extent doesn’t coincide with the physical space, but that relies on a mechanosphere of signal processing and emitting machines. The GNNS constellation (i.e. the global navigation satellite systems, which include American GPS, Russian GLONASS, Chinese BedDou, European Galileo and Japanese QZSS) belongs to the latter. Humanity went to great lengths to set it up in the course of the 20th century. It allows us to manage a global transportation system. Now, a substantial part of humanity tries to tear it apart, jamming not only GPS, but all frequencies of what we just recently thought of as our collective mental processes that ensured our grasp on a shared reality. We have turned into the bewildered observers of the self-destruction of the entire noosphere.

Whether GPS jamming and cyberattacks are as bad as tanks and missiles is a secondary question. The former often precedes the latter and, until we figure out a way out of this mess, our winding paths in the space of conflicts will only get thinner, and tighter.

Source: https://gpsjam.org

References

- Teilhard de Chardin, Pierre. 1970. Le phénomène humain. Paris: Éd. du Seuil.

- Goyushov, Altay. 2024. “Understanding tensions in Nagorno-Karabakh through a religious prism: a look back at the war of 2020 – English version”. Bulletin de l’Observatoire international du religieux (OIR, CNRS), No. 47., February 2024.

- TN. 2024. « Swiss Takes a Detour to Asia ». Travelnews. Consulté 14 mai 2024 (https://www.travelnews.ch/english-corner/26211-swiss-takes-a-detour-to-asia.html).