What follows is the text of my presentation at the ICHC 2015 in Antwerp, held on July 15th.

Abstract: That there exists a dialectical relationship between spatial representations and spatial practices is a familiar idea, which received extensive theoretical development by thinkers as diverse as Henri Lefebvre, Gunar Olsson or Franco Farinelli. My aim is to explore this relationship by focusing on the mutually reinforced development of road maps and of motorized individual transport in the 20th century. Doing so, I also wish to identify tendencies in contemporary mapping practices, which possibly fore- bode the emergence of a post-car world. In North America, Europe and its colonies, automobile maps for the individual driver evolve in the early 20th century, mostly from earlier bicycle maps. The first Soviet maps of the kind emerge after WW2. In the “West”, production and distribution is promoted by private companies, drivers associations and public actors with the aim of stimulating car-related consumption, local tourism, or the sense of national or continental identity. In the first stages of development maps help to make the car usable by identifying the most drivable road segments. Beginning in 1917 Rand McNally (USA) articulates its Auto Trails maps to a system of numbered highways, and is directly involved in the erection of corresponding roadside signs. This process, soon imitated in other countries, contributes to a general transformation of the lived space, in which spatial orientation comes to depend less on architectural and topographic landmarks and more on formalized signs, whose interpreta- bility closely depends on maps. The lived space evolves from landscape into a linear sequence of signs, well incarnated by objects such as the first on-board navigators Iter Avto (Italy, 1930) or Plus Fours Routefinder (UK, 1927). The process also involves a radical generalization of all mapped elements not directly accessible by car, while emphasizing car-related amenities (e.g. Guide Michelin, France, beginning 1900). In parallel – among the professionals of space – the development of zoning schemes in land-use planning intensifies, and at times enforces, the use of the car between large mono-functional areas. From the mid-1980s road maps are increasingly digitized and incorporated as onboard navigation systems, further participating in the ‘automobilization’ of space. Extensive car use allows the commercial development of these systems that, however, also push the frontier of the mappable itineraries while mutating into mobile phone applications. The StreetPilot app for Android and iPhone, for instance, considers public transportation options, such as trains, trams or busses when calculating pedestrian routes. Thus, while cartography has played an important role in making the car usable, it might well play a central role, today, in the evolution of a car-dominated space to a space of multi-modal mobility.

Introduction

First a couple of words about the context of the PostCarWorld project, in the name of which I have intervened. Our basic postulate here is that the car is not a mere physical object but a total social fact with many dimensions (cf. Mauss 1924). It is an object that can evolve along all these dimensions. That is what the architects, geographers, economists, urban planners and sociologists of our team are studying right now.

One dimension of the car is of course that of being a private property. This also also means that the car becomes something else through car-sharing or other uses of the same physical object.

The car is also a privatization of public space. A bubble of privacy similar to the suburban villa which has its counterpart in urban living and public transport where exposure to otherness occurs.

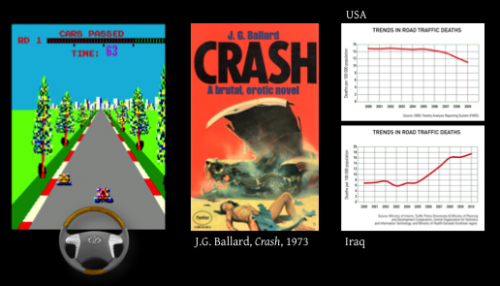

The car, as we know it today, implies a personal responsibility of the driver. Cars mean control by a human individuals of a very fast and very heavy machines moving through a complex traffic.

The car is a particular type of public spaces: service stations, motels, etc.

The car is a particular type of energy industry around gasoline that has superseded kerosine in the oil industry in the early 1920’s.

The car is a certain experience of speed in a linearity of movement. As opposed for example to pedestrian movement : which is more slow but actually gives you access to more things and options of direction at any step you make.

As illustrate the aerial images of Christoph Gielen, the car is a certain type of urban planning, which already brings me to maps. Because the map, especially as a 2D instrument, has played an important role in the practice of land zoning all around the world. This zoning practice has defined mono-functional areas, drawn on the map, implemented on the territory. These monofuctional zones are only useful for the human being when they are interconnected by a massive mobility, a multidirectional mid-distance mobility. The car has been, for a long time, seen as a an appropriate means of dealing with this mobility.

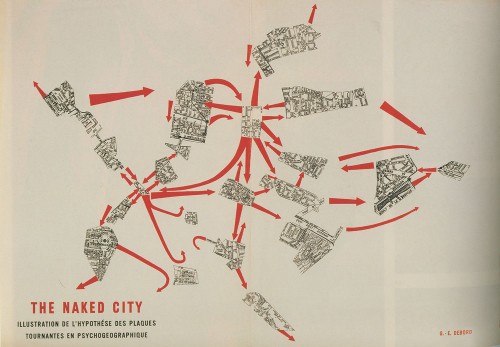

What I want to show is that the dialectics between autonomous motor vehicles and mapping devices has brought us a lived space in which we live today. And I think that in order to bring alternative spaces into being, we need to find not only technological solutions of mobility but also a new way to map the human space.

Saying so makes me think the frontispiece for the 2nd edition of Thomas Mores’ utopia by Holbein. In which you see an ideal world. This map is of course not only an a illustration of a piece of literature but also a synthesis of a social project.

Maps, in fact, have a great power to synthesize social projects and help them becoming our realities. Or as nicely says the historian Karl Schlögel in a different context “if you use maps in the right way, you’ll eventually end up in the world for which they have been made” (Schlögel Karl, Im Raume lesen wir die Zeit: Über Zivilisationsgeschichte und Geopolitik, Frankfurt a. M. 2003, 23).

The emergence of the automobile world in maps and spaces

Now let’s get to the heart of the matter. The emergence of the car world in maps.

Who and for whom?

The first question to ask is to know who made the car maps for whom. Let’s speak of the interest behind making maps and of their target public.

1:300.000 ~ 1910

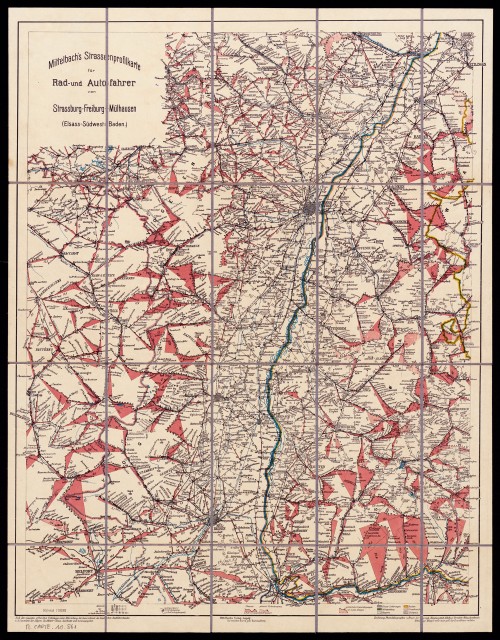

Interestingly enough, the first road maps of the late 19th century start to be made not for cars but for cyclists. Cyclists who, as you know, dispute urban spaces to cars today. There is a historical irony in the development of car maps.

Why is this so? Because the cyclists need drivable roads which are by far not as many in early 20th c. as today. Their interests converge with those of the car drivers. James Ackerman in several papers points out that the first driving maps are the result of the collaborative work of bycicle and car enthousiasts.

And this is true as much for North America as for Europe. In the figure above you have an example of an early 20th c. German map with road slope profiles. The roads are drawn in black. The red triangles on the map show you the steepness of the roads: a very interesting cartographic solution. And a useful one when driving a bicycle. But the map is already also meant to be used by car drivers. Who eventually take over and supersede the bikers on the roads of the World.

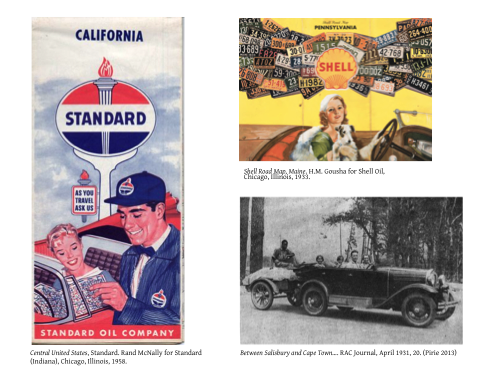

But final users are not the only ones to find interest in producing car maps. By the late 1920s, in the USA, oil companies have adopted the widespread free distribution of road maps as a major marketing tool.

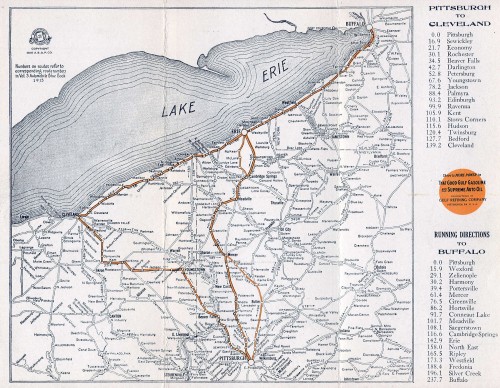

The very first generally distributed road maps are usually credited to Gulf Refining Company. In 1913 they opened the first drive-in gas station east of Pittsburgh’s and they began handing out road maps there. This is a Gulf map of the Pittsburgh-Buffalo-Cleveland from 1915. It is part of a series called The Blue Books, result of an enormous work of0 information retrieval from local – and generally anonymous – contributors. Please note that the topographic features have almost disappeared from theses pictures. Except for the lake Erie, you see only roads and toponyms. So there is a reduction of space to which I will come later.

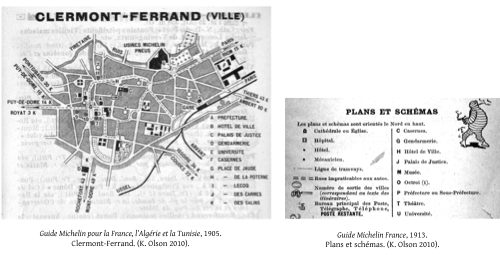

Now the same promotional logic is also at works in France in the case of the Carte Michelin. These small atlases were produced by the Michelin tire company as soon as 1900. Also in order to promote car travel and to sell its products.

On the map of Clermond-Ferrand you find, of course, « les usines Michelin Pneus » in the north of the city marked in dark black. You find also some touristic features such as the gardens near the University in the south that might be points of interest to touristic car drivers. Also note that non-drivable parts of the city have disappeared. You only see what you can reach with your car. Michelin wants you to use his tires, not your shoes.

Intersting here is that you also see the prefecture, post office, the Hôtel de ville, the Palais de justice as main features. This is not an obvious choice. But a hypothesis put forward by Kory Olson (2010) is that the Guide’s Michelin puts emphasis on the French nation’s bureaucratic infrastructure in the context of a recently reorganized 3ème République. Doing so, it comforts its car-owning bourgeoisie while giving them a good time and selling them tires. So i’ts both about touristic attractions, consumption, and national identity.

Strangely enough, though, as my colleague Quentin Morcette has pointed out during the conference, Michelin has produced only maps of city centers and not a global view of automobile France.

Speaking of values, in the USA too, we find traces of social realities in the car maps. The maps had usually accompanying artwork and text. These often associated car tourism and consumption of car-related goods and services to individual freedom, patriotism, family values and other big values of the moment. All of this was meant to stimulate consumption (see Ackerman). But it was of course rather aimed at a middle- to high-income white population.

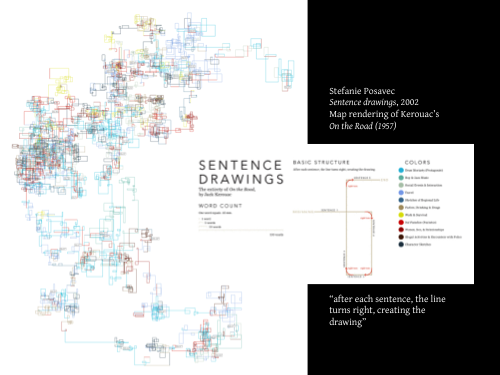

Nevertheless, road mapping is also how the car in North America has evolved into a cultural topos. This topos has not only reinforced old social norms but it also brought about social change and new ways of life about which we read today in literature. The contemporary map above shows you an example of mapping the novel On the road by Jack Kerouac. The London-based artist Stefanie Posavec shows the way in which we travel through the sentences of the book while driving the car along with Dean Moriarty.

In Soviet Russia, the logics are very different. You have a truck production starting 1917. In 1929, it is Henri Ford who sings with the Soyuz for the construction of the first automobile company called the Го́рьковский автомоби́льный заво́д (Gorky Automobile Plant) in Nizhny Novgorod. Production commenced in 1932 and lasted until 1936, during which time over 100,000 examples were built.

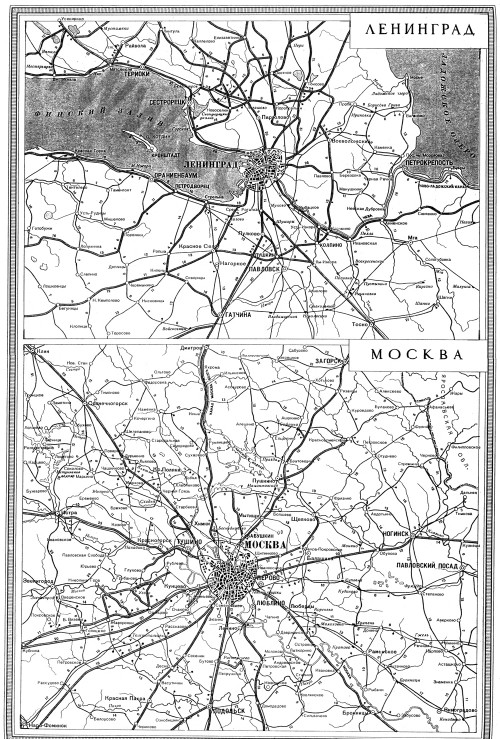

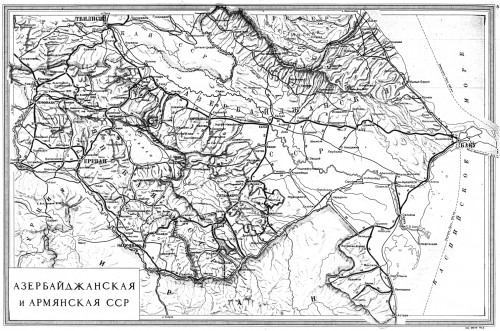

But the first Soviet specifically car-oriented road atlas dates to the 1940’s and is mainly military to my knowledge. It was made for the trucks and vehicles of the Red Army. These maps below stem from 1945 – a date by which the Red army had a fairly good idea about the road network of the Soviet union and beyond.

Please note, on the maps bellow, that the topographic features have almost disappeared from theses maps… with the exception with regard to topography in those regions where it plays an important strategic role, such as the Caucasus.

In civil terms, in 1950-1960s and even in 1970s a personal car was a dream of many citizens since the car industry was not sufficiently developed and output not many automobiles. The cars were distributed via factories, institutes and other organizations to their employees and there were long waiting lists of those who wanted to obtain one (Vinogradova). According to Твердюкова (2012), a running joke in the Moscow of these times is said to be that the muscovite took pleasure in his car only twice in his life: the day he finally got it, and the day at which he got rid of it; since it was difficult to park and neighbors could get upset about you having a car. By the mid 1960’s, there was in effect still only one car for every 238th soviet citizen. In the USA in the same year almost every second American owned a car (1 automobile per 2.5 inhabitats). Nevertheless, the first edition of a civil automobile atlas of the Soviet Union was edited as soon as 1958. Nevertheless, the traget audience of these maps was de facto concentrated in Moscow most of the cars were to be found (Твердюкова 2012).

The trasnformation of space

Now that we’ve seen some of the actors behind the scene of change of our space, let’s have a look at the concrete changes made to our perception of space by maps.

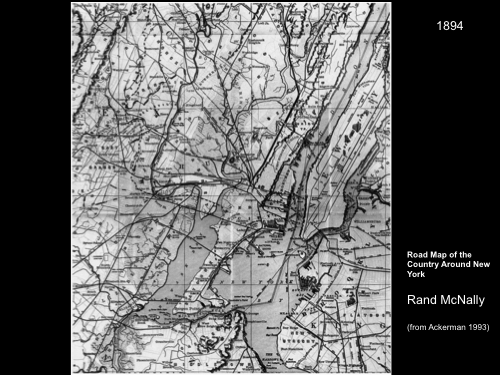

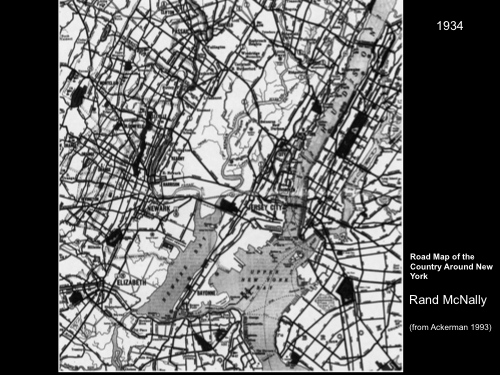

A central change, that James Ackerman stresses, was the already stated disappearance of topography. This becomes particularly apparent in a comparison of two Rand McNally maps of the country around New York. The first in 1894.

And then a map of the same region in 1934. Meanwhile, the Henri Ford industry introduced the model-T in 1908 which made the car accessible to a great amount of people.

What happens in space is: you are left with a set of numbered lines connecting toponyms and points of interest for the car driver.

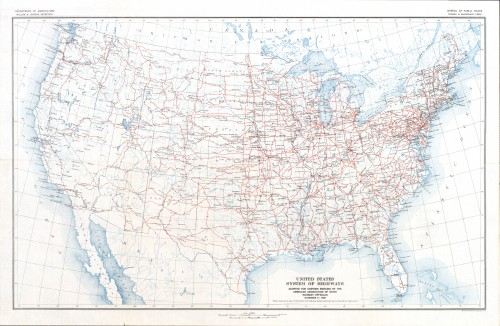

This is not only a cartographic evolution. Meaning it doesn’t happen only in representation. Map companies, such as Rand McNally actively participated in the implementation of road numbering of the US Highways, including the actual physical road signs that go with it. They wanted to assure the accuracy of its Auto Trails maps. So Rand McNally sent some of its employees to put these physical road signs in the field on some roads.

This work of road marking and numbering has been eventually taken over by the government in the USA. In 1925 a federal law has been proposed about the interstate highway system. This system has been formally adopted in 1926 and marked nationwide by 1928. So the process moves from the hands of private companies to the federal government.

In any case, as mantioned, space is transformed from an open topographic territory into a system of signs and connectors. In terms used by some geographers, our conception of space moves from that of a territory to a network. Space ceases to be an area of undisclosed possibilities and becomes a system of predetermined signs and paths that connect them.

Thast’s what Émanuel Lévinas would call “mettre fin au dire dans le dit”, if we go back to the terminology of 20th century phenomenology. (the process of saying is coming its halt in that which has been already said). We could also speak, with Gilles Deleuze, about the transition from a smooth space to a striated space.

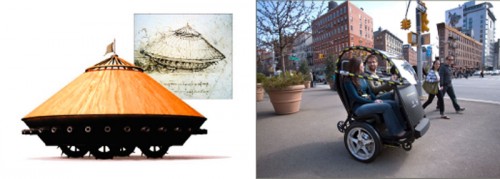

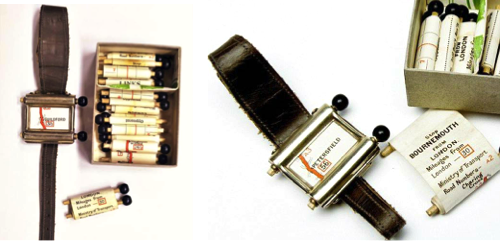

One of the great examples of this transformation for me is a small device called Plus Fours Routefinder that was produced in the UK in the late 1920’s. The image is self-explaining: you choose a particular roll with a road and then you drive along with it.

Of course, this is only as good as you don’t get lost. So there is a strong hypothesis here: the space in which you move is not a landscape but the shortest path line connecting your point of departure and your point of arrival.

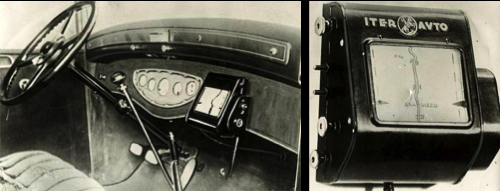

A more elaborate example was produced in Italy in the 1930’s. Called Iter Avto, it is connected to the mileage counter of your car and the map rolls out autonomously. As you proceed, direttamente, to your point of destination.

The role of maps in making the future of the space of mobilities

Now the image of the Iter Avto already brings us to contemporary GPS, and to my final question: what change in our use of space can be brought about by the mapping devices?

As the architect Burkminster Fuller said “You never change anything by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete” My question is whether a new model is emerging.

If we go further in the history of onboard car navigation, you find for example a device called Etak that debuted in the mid-1980s. It depended on mapping data stored on a cassette drive, with tapes. And each digital tape covered a section of a city. It was not connected to GPS, so you relied on dead reckoning to find your way: the user entered the location of the car where it was first installed, and took it on a short calibration drive. From then on, the system self-corrected: error accumulated in this manner could usually be reduced by checking to see if the current location and direction of movement corresponded to a street in the map data. The driver had to change the digital tape when the end of the screen was reached. So the driver became a kind of a processing unit between computer data, the urban road system, and the wheel of his car.

The very first device actually connecting to the GPS was installed by Toyota in 1991. Made by Alpine Electronics in the US.

In between navigation systems are becoming harder to sell because of a rising offer in terms of software navigation systems on mobile phones. Some of theses system, like Google maps, are for free, so the traditional producers of professional GPS try to compete, by adding extra features, for instance, such as information on gas prices in the surrounding area, navigation functions such as a tour guide, that shows information on landmarks and reviews of hotels and other services nearby. One such system, currently developed by Mercedes Benz, is gesture-controlled. This means that, through the map, manufacturers also explore new ways of interacting between the human and the machine.

And this brings me to one of the important ways in which maps could change the total social fact called car. What I means is that maps will most probably become the new steering wheels of cars that no more require a driver, with a wheel, but they drive you themselves to a destination selected by pointing on the onboard map. The driver becomes a passenger and can again observe the landscape on the right and left of the road, even start to interact again with the surrounding environment.

But yet another aspect of change, more important to me, is to be found in map software on mobile devices. Some of these software offer not only exclusively pedestrian or exclusively car-centered itineraries, but that are able able to combine diverse options.

If you move through a city as a pedestrian, already existing applications give you the best pedestrian route by integrating also public transportation options, such as trains, trams, or busses in your itinerary.

Ironically, bicycle maps have brought about car maps taht have brought about navigation software in the private use. And today the navigation software is perhaps to become our way out of a car-dominated space.

Thus while cartography has played an important role in making the car usable, it might well play a central role, today, in the evolution of a car-centered space to a space of multi-modal mobility. And get us back from the network to the territory.

![strip map example the road from London to Portsmouth, “actually surveyd and delineated by John Ogilby Esq[ire]: His Ma.ties Cosmographer.” (1675)](https://ourednik.info/maps/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/1024px-Ogilby_-_The_Road_From_LONDON_to_the_LANDS_END_1675-500x361.jpg)

Aknowledgements

My thanks for updates to this paper concerning Soviet maps go to Nataliya Vinogradova from the Russian State Library in Moscow.

Further reading

Akerman James R., 2010, Cartographies of Travel and Navigation, University of Chicago Press.

Твердюкова Е. Д., 2012, “Личный автомобиль как предмет потребления в СССР. 1930-е — 1960-е гг.” Новейшая история России / Modern history of Russia. 2012. No1