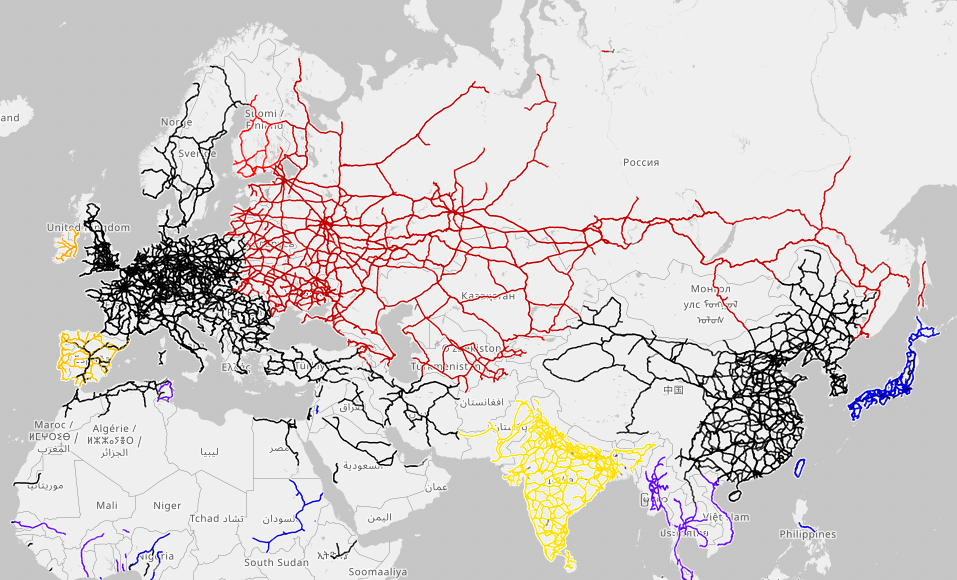

A look at the global map of rail track gauges immediately reminds you of the current invasion of Ukraine. There is a material substrate of the putinist nostalgia of the Muscovite Empire. Far more than a purported linguistic or cultural proximity of the ex-Soviet states, this substrate of steel paves the way for geopolitical ambitions. Rail is a concrete military asset that accelerated the movement of Russian troops across Ukraine. The importance of Ukrainian reconquest of logistic hubs, like Lyman or Kupyansk, acquires most of its meaning in this context. It comes with no surprise, too, that Ukraine follows up on its pre-war plans to adapt its major rail lines to the 1435 mm European standard, and considers adapting its whole system. This development will have the double advantage of stalling any further aggression spreading across the 1520 cm gauge Muscovite network, and of tightening Ukraine’s integration with Europe. With much of the country’s infrastructure destroyed, its upcoming reconstruction presents an opportunity for accelerating this plan. This will not offer absolute protection, of course, but a strong logistic deterrent; while narrowing track gauge is common, expanding it implies replacing all sleepers, which Russians would need to undertake on their next nostalgic rampage. The European Union further conducts a feasibility study for the 1435 mm railway in Moldova. The project Rail Baltica will use the same gauge and connect Berlin to Helsinki via Warsow, Kauna-Vilnius, Riga and Tallinn, avoiding the Kaliningrad enclave and Belarus. It began in 2011 and geological surveys, station construction and archaeological excavations are well underway.

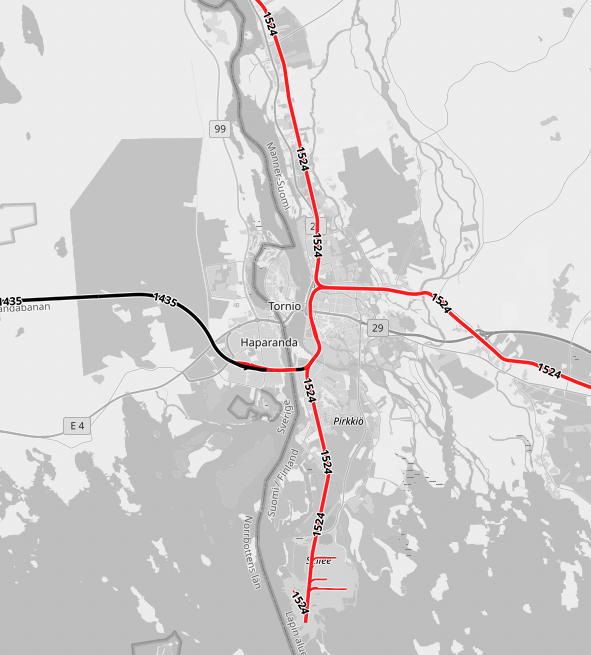

Finland: Torn Between Empires, Freed by the Union

That being said, other parts of the map are worth a closer look. Finland, for instance, inherits a 1524 mm gauge from the times of its subjugation to the Russian Empire. After the October revolution of 1917, it managed to convince Lenin and the early Bolshevik government to accept its independence. Thus, when the Soviet Union reduced its gauge to 1520 mm, Finland kept the imperial standard. Since then, the Finnish rails are drivable by – yet still less welcoming to – the boggies of Russian trains, and their gauge also stops cold any nostalgia for the Swedish Empire (that colonized Finland until its defeat by imperial Russia in 1809). Because you never know. Some Finnish officials, like Päivi Elina Wood, call for an adaptation to the European standard; with regard, again, to food supply and other security concerns induced by Russian aggression.

The Broad Tracks of the Celts

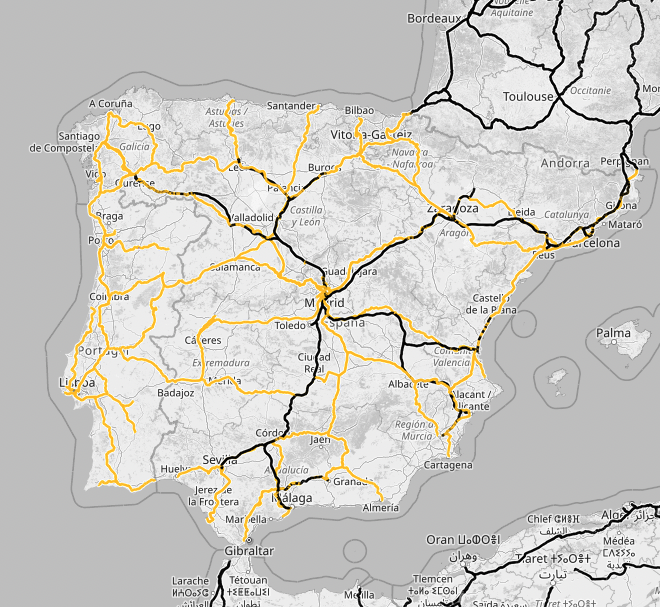

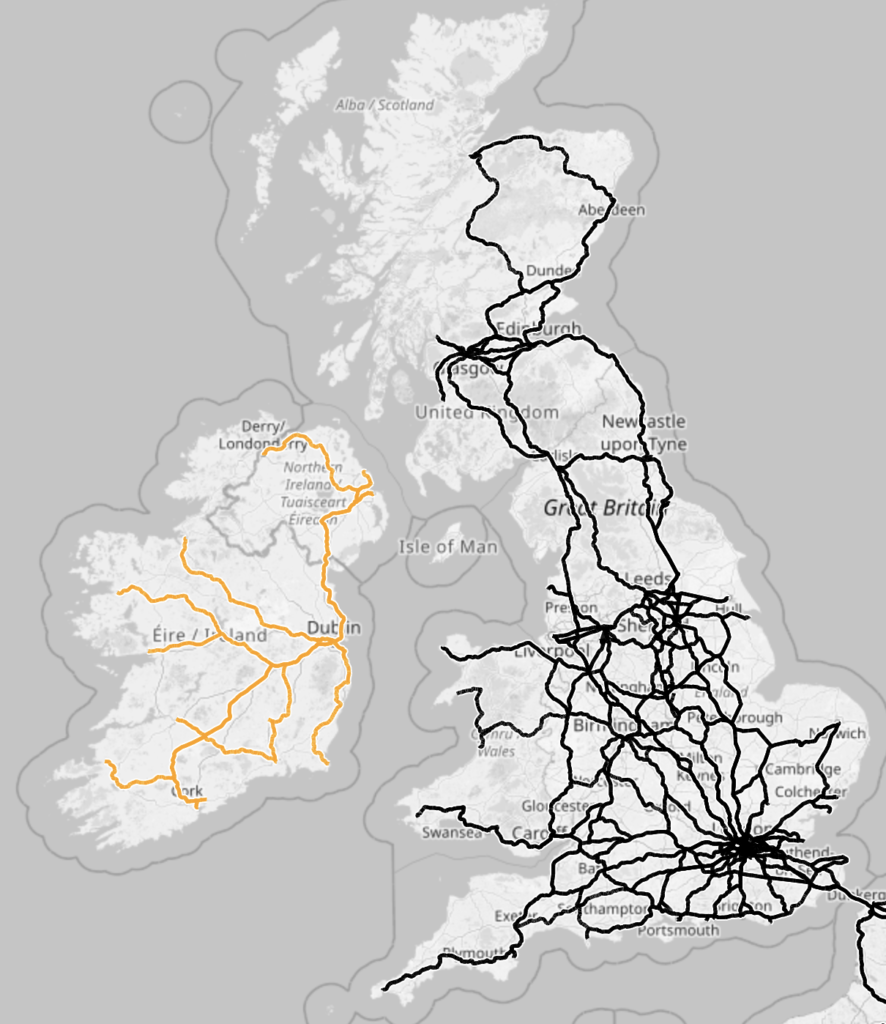

Three other exceptions stand out in the European Union. Spain and Portugal mostly use the Iberian gauge of 1668 mm, a compromise between 6 pie castellanos (1672 mm) and 5 pé português (1664 mm). Thirty-two years of fascist dictatorship in Spain and forty-one years of as much in Portugal did not help connecting the peninsula to the evolutions happening on the rest of the continent. But European trains now penetrate Spain on the main Barcelona-Madrid-Seville lines connected through Perpignan. The Spanish constructor Talgo has become a globally acclaimed expert in variable gauge wheelsets.

Portugal and Spain have a strong Celtic heritage. Ireland even more so, and it too, has a historical preference for wide gauge tracks (1600 mm). Being an island, its standard is rather arbitrary and less impactful, though it might become an issue if anyone makes earnest with plans for an Irish Sea Bridge. On the other hand, it could remain useful should the British go bonkers and decide to let off steam built up in the aftermath of Brexit by re-invading their past colony.

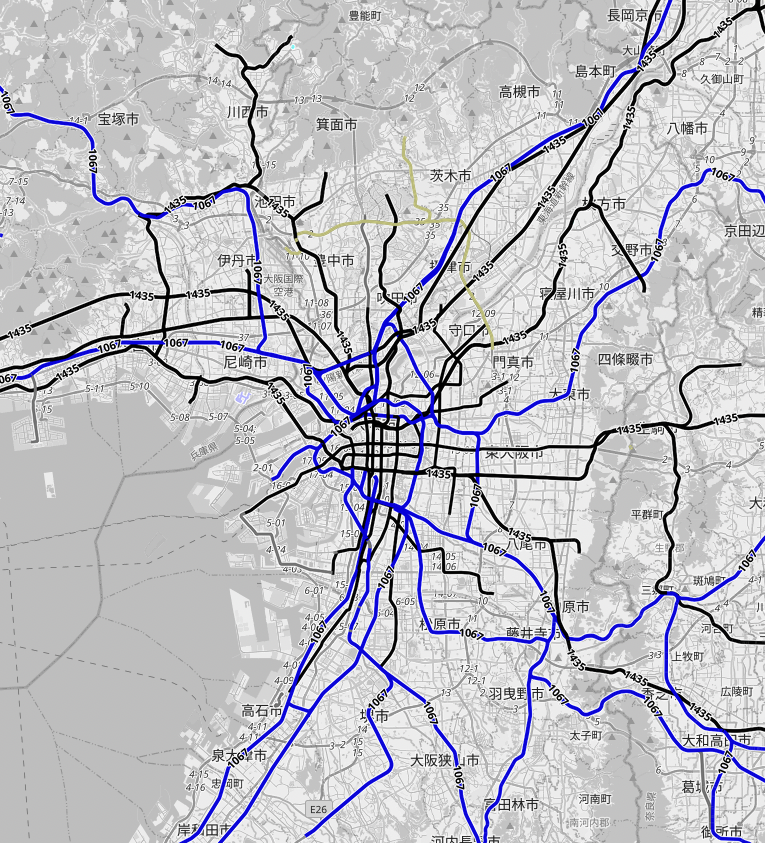

Japan’s dual gauge

Japan, another island, uses a narrow 1067 gauge for most of its rail network. But the Shinkansens drive on the same “Stephenson” gauge (1435 mm) as the much slower European trains, for better stability at fast speeds. This dual gauge in Japan makes total sense. Broad tracks allow fast speeds on main routes, the narrower ones are cheaper to build in Japan’s hilly topography and allow for sharper curves.

The mountains and the cities

The same issue applies to Switzerland, a country who made itself expert in public access to it mountains. Until the 19th century, the local population believed that the peaks of the Alps were inhabited by bandits and the devil himself. Then the romantic tourists from Germany and England came, and the Swiss realized that the infertile snowy peaks can actually generate money. So they defied their topography, first by drawing every detail of it in the two cartographic surveys of the generals Siegfried and Dufour, then by building tracks up to the Jungfrau Joch. Gauges as narrow as 800 mm give access to the heights, while the Stephenson standard gauge in the valleys connects the Swiss cities and the rest of Europe. The perfect compromise.

The broad trains of the ex-Raj, Chile and Argentina

Governor-General James Andrew Broun-Ramsay, the 1st Marquess of Dalhousie Castle, found the winds of the British Raj quite strong. So much that they would easily blow away light wagons drawn by a narrow locomotive, he fancied. And so it came that the track gauge in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal still bears full 1676 mm. The most extensive and most largely populated part of the British Empire never experienced the “standard” version of the Empire’s greatest invention.

To cumulate the strangeness, the sole other countries that adopted the “Indian broad gauge” – or “trocha ancha” – were Argentina and Chile: ex-colonies of Spain, the British Empire’s rival. Both countries also use a narrow gauge in the north. In contrast with Japan or Switzerland, this has less to do with the Andean Cordillera than with a stubborn competition of competing railway companies.

China and Korea : a Historic Godsent for the TGV

China and Korea also sport the same gauge as Europe on the main lines. Their construction has been initially conceded to British, French and German companies. Some early tracks in China were also laid by Russian engineers, who built the Chinese Eastern Railway as a shortcut to Vladivostok; with, of course, a Russian imperial gauge. Then the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 happened. The Japanese won, and then regauged the line to the Stephenson standard. Half a century later, this turned out a godsend for the French constructor Alstom, who sold the TGV to both China and Korea.

As for the relations between China and Russia, well, the friendship of Jinping and Volodia might be “limitless”, but Volodia’s trains will never drive on Jinping’s tracks. While China, too, produces variable gauge wheelsets.

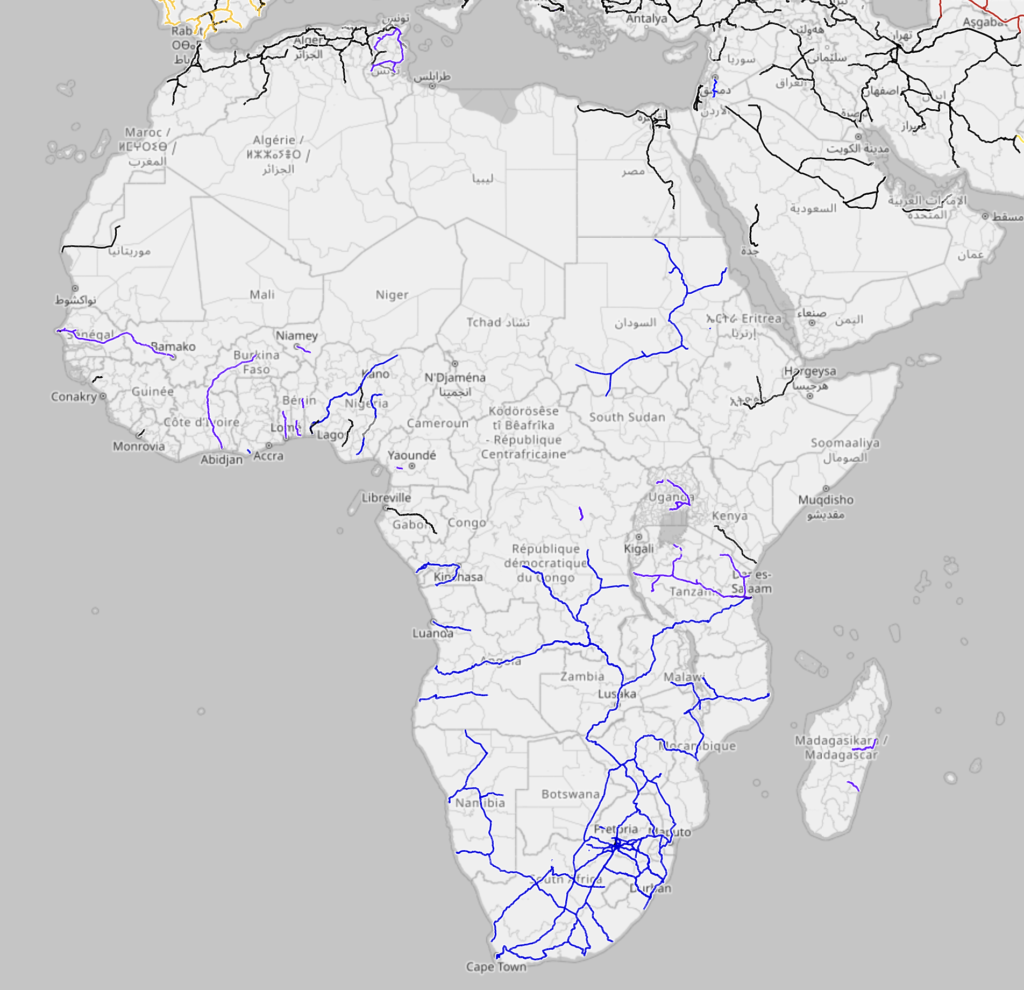

A continent to construct

All is left to be done in Africa in terms of continental public transport. The north of the Maghreb is relatively well connected, using the Stephenson gauge (1435 mm) inherited from the French Empire. Nothing in Libya, depleted by forty years of reign the Gaddafis and by Western sanctions, with little hope for positive development in the near future. Separated from the Magreb by this Libyan rail desert, Egypt’s network remains disconnected despite using an identical gauge. Another national network with international ramifications spreads from Johannesburg in South Africa with a gauge of 1067 mm. For the rest of the continent, only network sprouts shoot from the shoreline in Dakar, Abidjan, Lomé, Cotonou, Lagos, Port Harcourt, Libreville, Luanda, Moçâmedes, Mombasa, Djibouti or Port-Soudan. This situation impends trade between African countries (only 15% of total trade is continental), and favours trade with ex- and want-to-be- colonial powers in Europe and Asia. The best way for Africa to defy the world would be to unite, starting with its railroads.

The self-defeat of stubborn capitalism

Last on the list and contrary to Africa, Australia has long had the financial means to build a denser rail network. But the Australian continent has long suffered from a disorderly competition between rival colonies, each jealously guarding of its own gauge. This ruined the Australian railroad and has never been resolved, leaving continental transport to the road and its multi-trailer “road trains »: a further contribution to the continent’s appalling environmental record. Neither nostalgia, nor defiance here, just plain inertia of stubborn capitalism that blights all attempts at international agreement on standards of any kind.

PS: the Standard Behind the Standard

One old question remains open: where does the Stephenson standard of 1435 mm, used in two thirds of the world’s railways, come from? One theory is that it goes as far back as the wheel spacing of Roman chariots. As centuries went by, these chariots left ruts in the roads of the ancient empire. A perfect example of what I’ve theorized elsewhere as the phenomenon of the imprint:

In turn, matter is a soft body and a firm body. Our landscape is an imprint of human, aquatic, geological, climatic and botanical processes. The pyramid and the ziggurat bear the imprint of the mountain; their hollows are the imprint of the cave on the mountainside, which was imprinted in the thinking of humans architects during the millennia when it was the only thing they knew about, to house their magical paintings. These paintings themselves are the imprint of a bygone world that, through them, continues to haunt our nostalgia. The Gothic temple bears the imprint of the forest and the treetops that meet under the sky. Space is a medal struck in the effigy of a story that unfolds on multiple time scales.

Centuries after the Roman empire left the British isles, English wagonways kept on using the wheel spacing of the Roman roads. This didn’t change with the introduction of tramways and train carts, though the steel rail demanded a more exact standard. George Stephenson was the son of a low-income fireman and his spouse, both illiterate. He realised the value of education and paid to study at night school to learn reading, writing and arithmetic. He made a career as a designer in the harsh times of the Industrial Revolution. He first used the gauge of 1422 mm in 1814 for his locomotive hauling coal on the Killingworth wagonway. When he built the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1825 and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in 1830, he widened it slightly to 1435 mm to provide greater stability, yielding the “Stephenson standard”, that spread with the British empire and the influence of its engineers.