English translation transcript of my conference given in French at the CERN Globe on September 22nd, 2022, and based on the eponymous book from 2019.

Tonight, I propose to talk about two ideas, two concepts. The first one you already know: the concept of utopia. The other concept, which I propose to introduce, is the concept of hypertopia, which can be likened to a state of omniscience that is not necessarily pleasant, a state of drowning in information, which I propose to see in detail in the second part of my presentation.

But I will begin with utopia. This without trying to remake the whole history of utopias, which is very long, from antiquity to the present day, from Plato to Thomas More, to contemporary ecotopias. I will not dwell, either, on Orwellian dystopias and others, which abound in literature. I am far from being a specialist in the history of utopias and dystopias. What I am going to propose instead is an oblique look. Another way of using the concept of utopia, which will allow us to use it in both directions of time, to talk about other mechanisms of our thinking and of our political imaginaries.

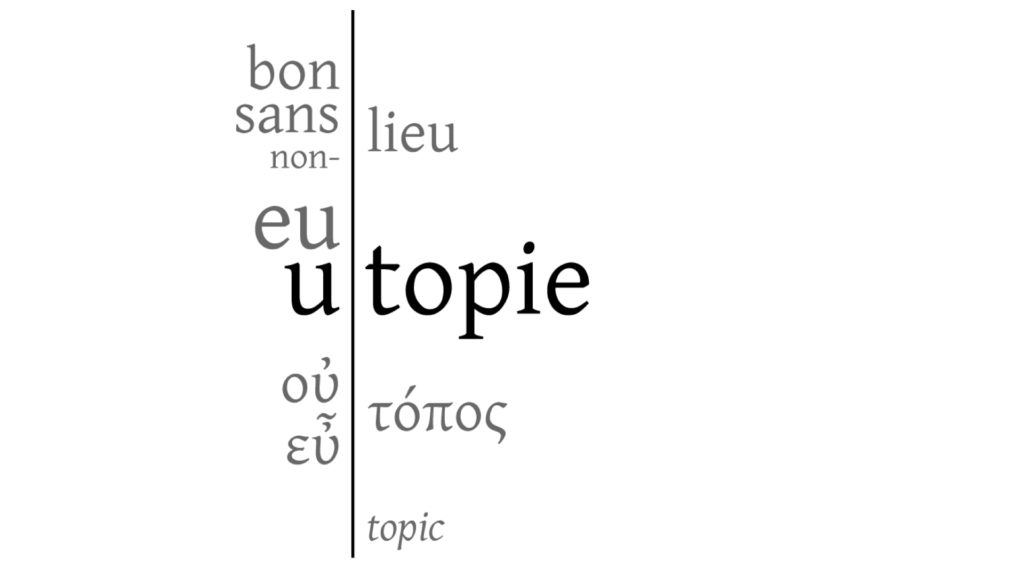

Let’s start with the word Utopia. This word appears first as the title of a novel, written by Thomas More, which appeared in the 16th century. This novel describes an ideal society. And its title is a word first composed by the root topos, place. Before this root, an ambiguous prefix :

- if we pronounce it in German, we hear /utoˈpiː/, where /u/ is a privative prefix; a negation, which makes utopia a non-place.

- if we pronounce it in English, we hear /juːˈtoʊpiə/, with the same prefix as “eulogy” or “euphoria”, thus with the meliorative prefix /juːˈ/, which means “good” or “best”, which makes eutopia the best of all possible places.

The second word is also ambiguous: topos can be, indeed, translated as “place” or “location”, but also as a “part of a book”, the “foundation of a reasoning” or the “subject of a speech”, and gives the root of the English word “topic”.

Utopia is therefore both the best of all possible narratives, but also a discourse about anything and nothing. There is always genius and stupidity in a utopia.

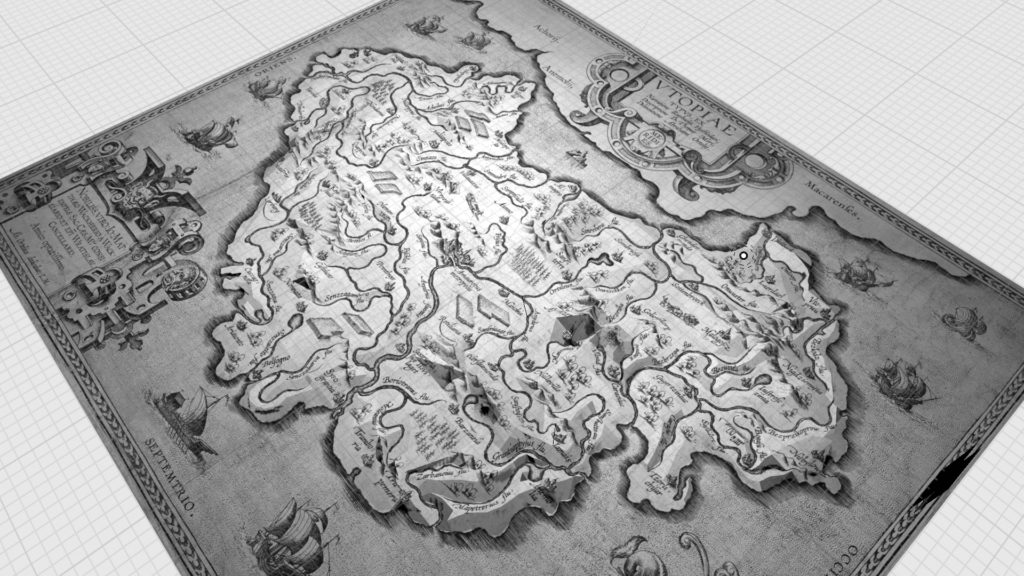

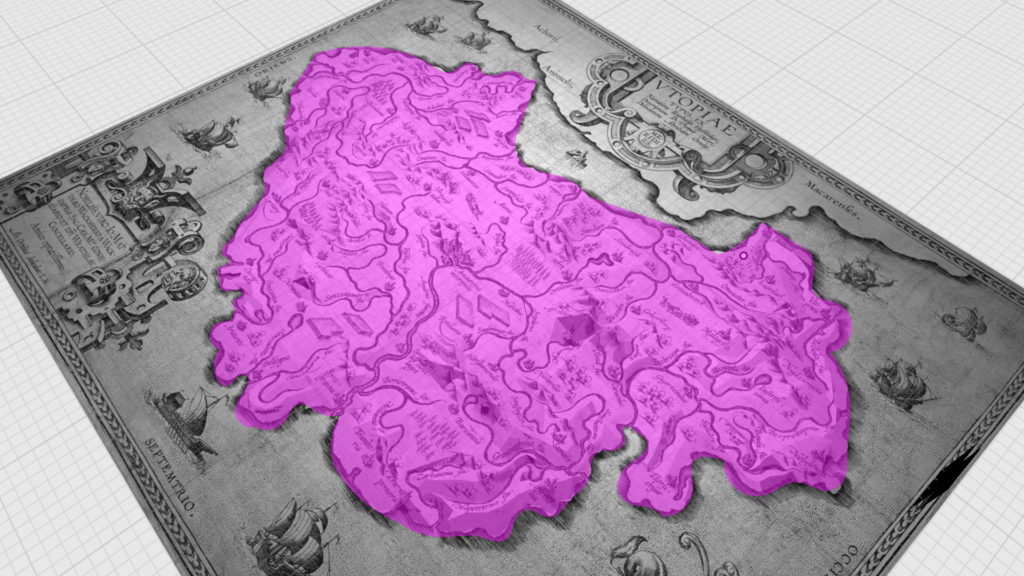

The original utopia, the one described by Thomas More, was an imaginary island off the coast of the Americas. Let us note that this topography is very telling about utopias. Because a utopia is, first of all, an island, and therefore something detached from reality. But at the same time, it is an island close to the coast, therefore visible from reality, like an ideal space, that we can look at, and that we can dream of joining.

Today, when we hear the word “utopia”, we usually imagine an ideal society where we could live. But there is often, also, a melancholy in this word “utopia”, because we consider that this ideal is unattainable and that it will never take place.

Finally, and especially today, there is mockery in the word “utopia”: if one wants to denigrate a project, one will say that it is utopian. If one wants to reject a proposal for an alternative organisation of society, one will say that it is “utopian”.

Generally, we will reproach, to the utopians, not to have taken into account all the parameters. Not to have anchored their ideal in the topography of the real world. That said, one can always wonder if it is really the utopia of the utopians which is limited in its conception, or then, if it is not rather the reality of the realists which would miss overall vision.

I’ll give you a brief example: if you say today that it would be great to live in a world without cars, many people will retort that it’s a utopia, and that you are completely crazy. They will say, “But how are you going to go shopping at the supermarket or take your children to school?” At this point, you can answer that there are cargo bikes, but they’ll tell you: “you’re crazy to expose your kids to traffic”. As if the people who say such things just couldn’t realise that, in a world of cargo bikes, there would be no more dangerous car traffic. And that without cars, there would be no supermarkets in the suburbs but many more stores in the city.

In this sense, to call something utopian is often a way of denying the possibility of a structural and systemic paradigm shift. Conversely, what distinguishes utopias from the politics of small changes is precisely to imagine not the change of an isolated parameter, but to imagine an entire society that functions with entirely different rules.

This condition of utopias means that, when one tries to set them up and live in them, it usually happens only in small groups of people, in a rather isolated place, where one can, precisely, test not a specific technology and practice, but a total model of an entirely different society.

The pictures above show a Swiss experience in Monte Verità, Ticino, at the beginning of the 20th century. A farming and spiritual community was established there. To tell the truth, they were children of wealthy families from Germany, who had bought the land to escape the industrial world and found a community based on theosophy, Taoism and Buddhism. They were vegans, practiced nudism, and debated new forms of society. In the 1910s, however, many important intellectuals stayed there, including Lenin, Trotsky or the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin. It was stimulating on the scale of this community.

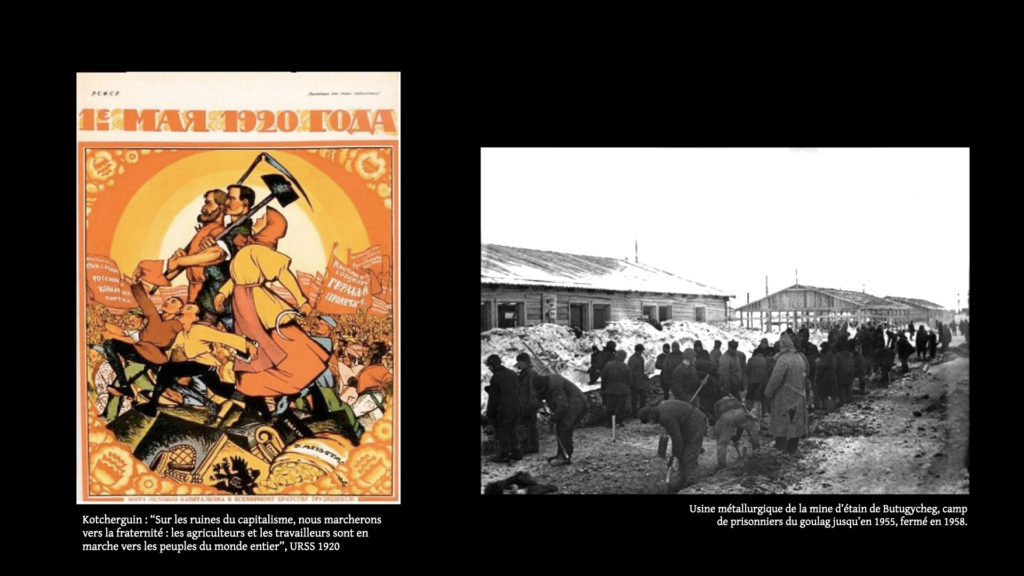

The problem with utopias is that when we try to put them in place on a larger scale, like that of entire countries, they seem to systematically lead to horror. This is what the 20th century seems to show us. During that century, we saw technicist utopias turn into war machines. We saw collectivist utopias turn into gulags of forced labour.

Here we are, now, at the beginning of the 21st century, with a civilisation that is suspicious of utopias. Either we imagine them as idiotic and unrealistic constructions of lunatics. Or, worse, we fear utopias like totalitarian regimes where such lunatics would have seized power to impose a limited model of society on all their fellow citizens. Nowadays, the appeal of utopias has withered if they are not regarded as downright scary. It is as if we had turned away from the future and that we had stopped imagining different worlds, utopias of the future.

The Past as a Substitute for Utopia

Yet we have not given up utopias. And this is where my proposal to widen the notion of utopia comes in. Because I realised, with a certain amount of anxiety, that any geographical place could serve as a utopia. In fact, the most widespread form of utopia, at the moment, are utopias that have turned their gaze from the future to look backwards, while continuing to talk to us about the future.

I will illustrate some of the geographical paradoxes that this can generate.

What I will try to show you, more broadly, is that we can apply the concept of utopia not only to political and societal projects, but also to other structures of thought, to many other ways of representing space and geographical places through time.

We are not far from the utopia of the “lacustres”, which was a theory at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century.

The “lacustrine” is a national myth founded by the archaeologist and theologian Ferdinand Keller, who developed it after the discovery of the remains of pillars in the lake of Zurich in 1854. In short, the ancient Swiss would have been a people of “hard-working, orderly and sociable”, as opposed to the “savages of Australia and the Americas who live carelessly from day to day, or who fight and devour each other”, according to the words of another researcher, Karl Dändliker, a professor at the UniZH. These peoples would have been collectivists. The collectives would have built a system of platforms on stilts in the lake, after which each family would have built its private house on the collective work. So this is the bourgeois ideal projected on the 50 millennia before Christ.

Afterwards, to be completely fair: at that time, we have just come out of the civil war of the Sonderbund and the Swiss authorities are looking for a basis for national unity. But this foundation is utopian, in the sense that I defined at the beginning of my presentation.

A little later, starting in 1927, a Zurich anthropologist and eugenicist named Otto Schlaginhaufen began to take skull measurements on contemporary Swiss people, in an attempt to find out what “our ancestor” to all of us, homo helveticus, must have looked like.

This utopian ancestor had, of course, like Professor Schlaginhaufen, a round face and brown hair. It should be mentioned that Schalginhaufen was president of the “Swiss Foundation for Research in Heredity, Social Anthropology and Racial Hygiene”.

And homo helveticus was strong, healthy, hardened, “tough as nails”. He ate crystal-clear water, fruit and simple dairy products. He had a brilliant mind, but he was not whimsical. “The long days of work turned him away from vice, preventing idleness and thus strengthening morality and virtue”.

This is the kind of idea that was considered credible in Switzerland not only until 1945 and the end of the Nazi ideologies, but until 1960, when Schlaginhaufen published his last works.

So, if we summarise, there would be an ancestor of all the Swiss, a perfect human in every respect, and his people would have lived in Switzerland for 20’000 years. Which completes evacuates a most basic fact which could have come to the minds of university professors: the fact that 20’000 years leaves time for several massive migrations on the scale of the continent, and even more so on the scale of the Alpine region.

But there is stronger than the Homo helveticus! For example, the dinosaurs.

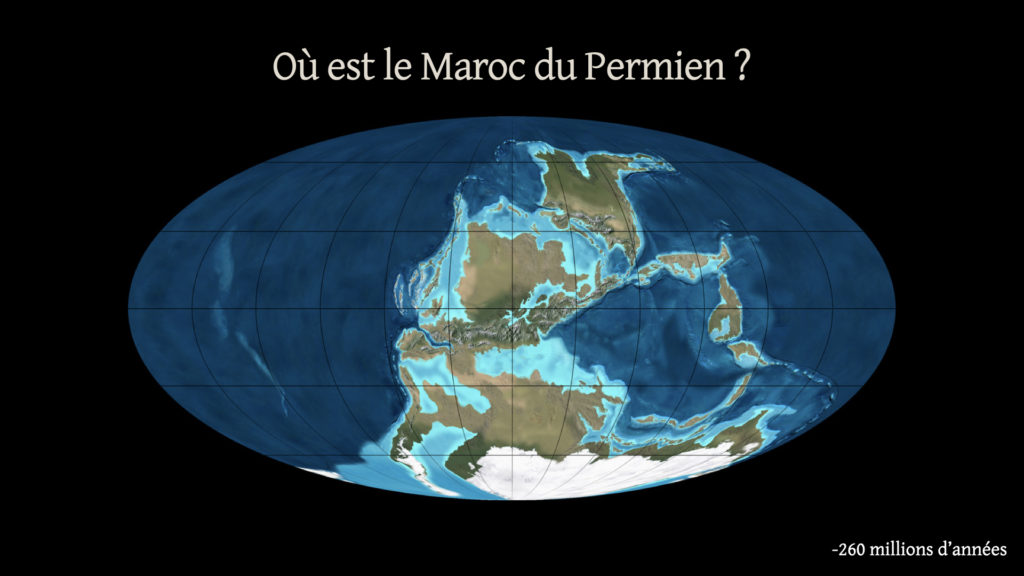

Some time ago, I came across an image that showed three dinosaurs: a Gorgonopsian trying to intimidate Arganaceras, a Pareiasaur. On the front, under the fern shelters, hid a small land reptile, Captorhinus. The image was titled “The Permian fauna of Morocco”.

When you see such images, you have to wonder where Permian Morocco is. The problem is that the continental plates have had time to move for 260 million years. You will have understood: “Morocco of the First” does not refer to anything. It is a utopia.

And yet, we continue to fantasise about the permanence of the nation. To project ourselves in a utopia of the permanence of nations, and not only in this utopia. We tend to project all our knowledge of the past onto maps, onto continents, onto contemporary topographies, assuming that these topographies are eternal and that they all resemble our own, whereas there is nothing permanent about them. Whereas everything changes, permanently.

So, if we continue to think about dinosaurs without making the effort to imagine the world of dinosaurs, our vision is utopian, we understand history from a space where it did not take place.

Unless we make an effort to be constantly vigilant about the impermanence of our universe.

Let’s take another example. You probably know the legendary oath of the Rütli in 1291. In the founding myth of Switzerland, the Confederation was born when three cantons (Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden) united to oppose the subjugation by a mythical enemy: the Habsburgs. When one hears Habsburg, one imagines an immense empire that ruled over all of Austria, Spain and the Netherlands.

But where were the Habsburgs in the 13th century?

All this remains a purely theoretical and basically harmless error when one speaks about the Moroccan dinosaurs, or the secular fight of the Swiss against the Habsburgs. It can become more serious when the utopia crystallises a frustration.

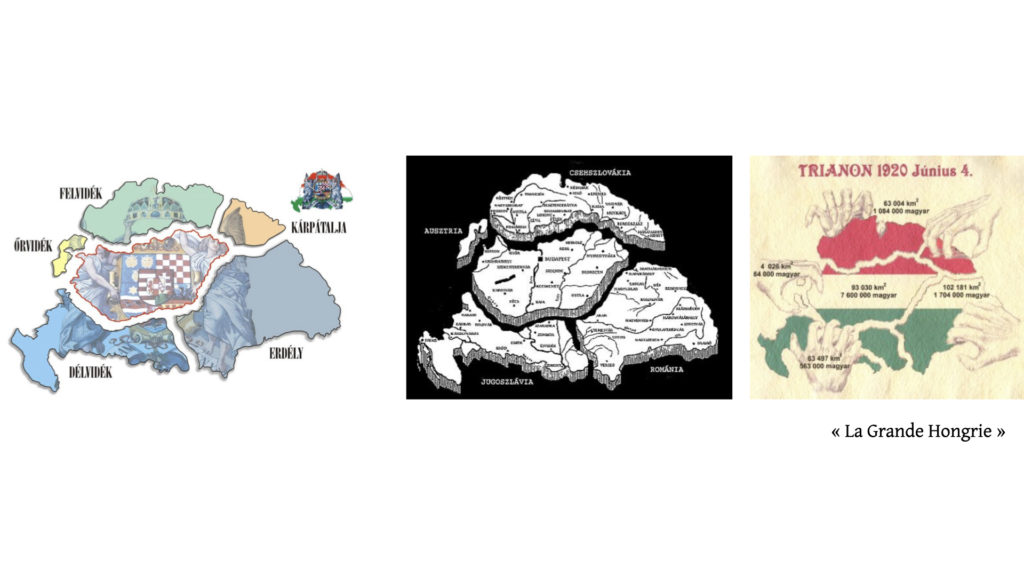

For example, in Greater Hungary, a territory that more or less belonged to the Habsburg crown until the end of the First World War. For many Hungarian irredentists, it remains the real Hungary. They would like to get it back from Slovakia, Romania and Croatia.

Of course, you also have “Greater Serbia” or “Greater Romania”.

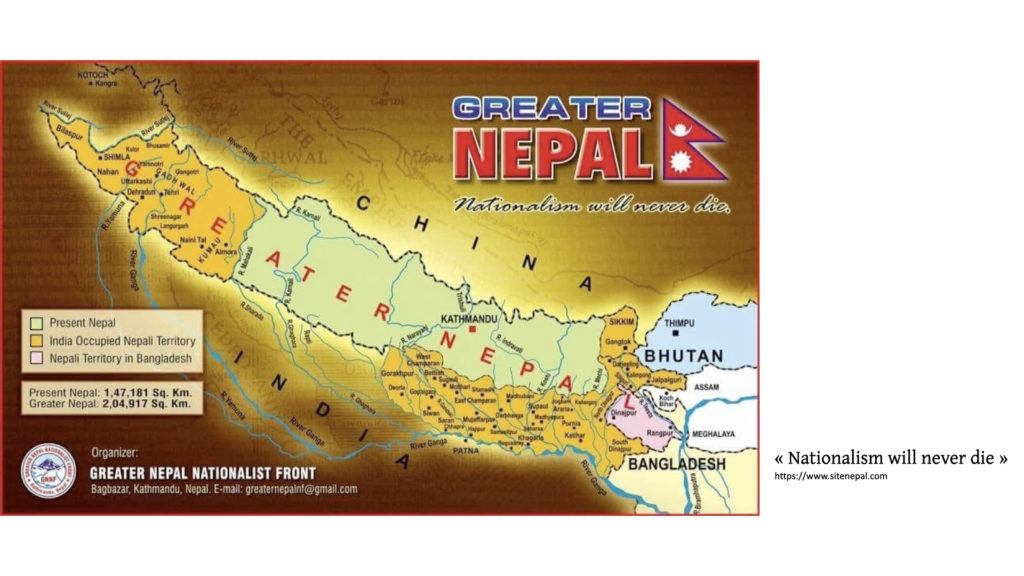

You also have the “Great Nepal”.

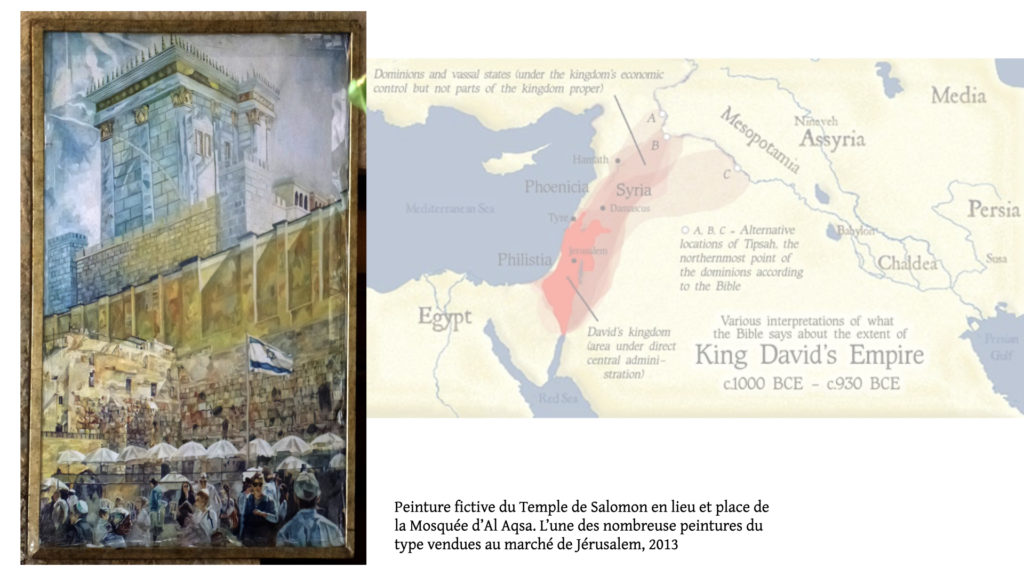

And we must not forget the Great Biblical Israel and the Temple of Solomon rebuilt on the Esplanade of the Mosques.

Don’t misunderstand me. I don’t believe that all these things are pure idiocy. It is, I think, rather, an immense nostalgia. A nostalgia induced by the impermanence of our world, by our difficulty in finding our bearings in change, in building an identity, in planting our roots. There is a nostalgia for space and places that I find extremely well illustrated in this short text by Georges Perec :

I would like there to be stable, immobile, intangible, untouched and almost untouchable places, unchanging, rooted; places that would be references, starting points, sources:

extract from ‘Espèces d’espaces’, galilée, 1974.

My native country, the cradle of my family, the house where I would have been born, the tree that I would have seen growing up (that my father would have planted the day I was born), the attic of my childhood filled with intact memories…

Such places do not exist, and it is because they do not exist that space becomes a question, ceases to be obvious, ceases to be appropriate. Space is a doubt: I must constantly mark it, designate it; it is never mine, it is never given to me, I must conquer it.

My spaces are fragile: time will wear them out, will destroy them: nothing will resemble what was, my memories will betray me, oblivion will infiltrate my memory, I will look at some yellowed photos with broken edges without recognizing them. There will no longer be written in white porcelain letters stuck in an arc on the mirror of the little café on rue Coquillière: “Ici, on consulte le Bottin” and “Casse-croûte à toute heure”.

Space melts like sand between the fingers. Time takes it away and leaves me only shapeless shreds:

To write: to try meticulously to retain something, to make something survive: to tear off some precise snippets from the emptiness which is digging itself, to leave, somewhere, a furrow, a trace, a mark or some signs.

In the words of Georges Perec, this nostalgia is sublime and moving, of course. But our tragedy is that power-hungry people use this nostalgia. They exploit the longing of their people at the expense of those people and at the expense of the international community, promising to cure the longing with territorial solutions.

A particularly sad example is on all of our minds right now.

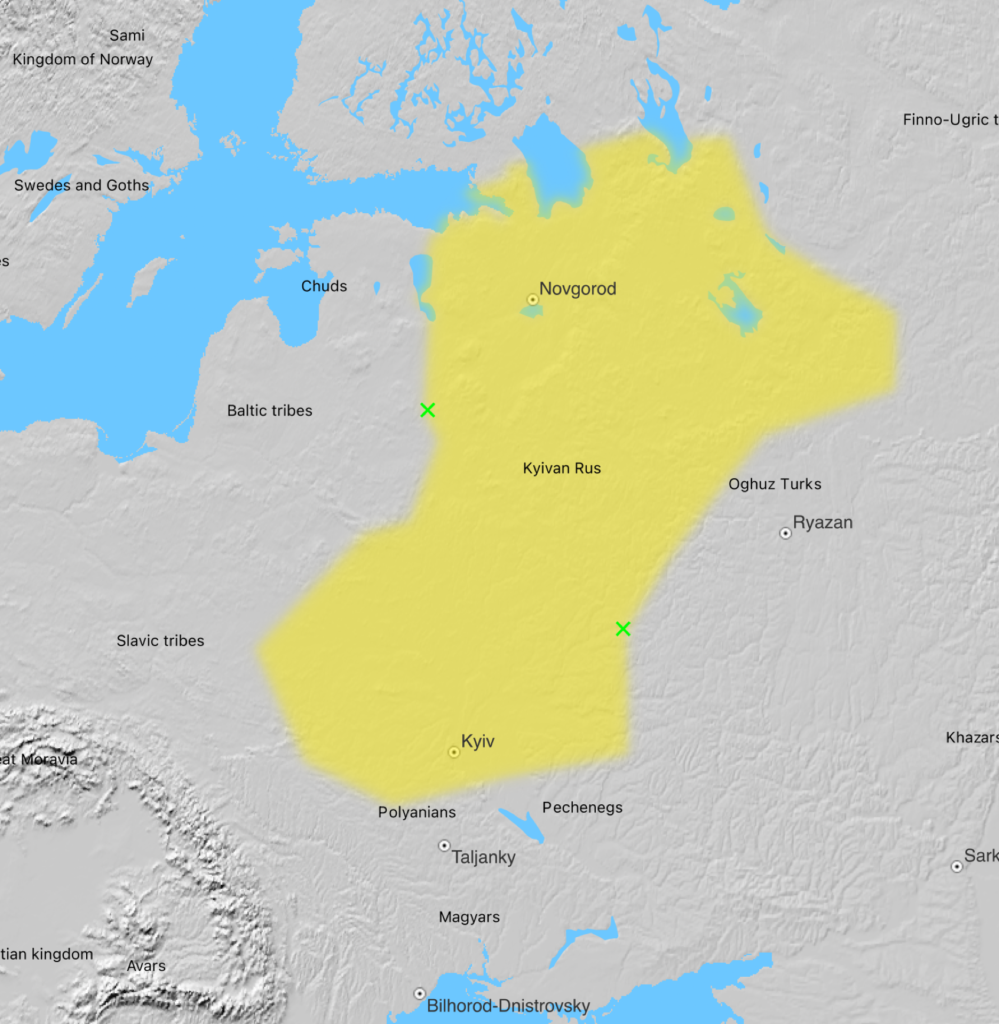

Once upon a time, in the year of the Lord 900, existed a pagan kingdom founded by Vikings, a kingdom that was called the “Kyivan Rus”. Note that this kingdom did not include Moscow, which did not exist at the time of its foundation.

Less than 300 years later, this Kyivan Rus was swallowed by the Mongol Empire, which occupied almost all of Eurasia in the middle of the 13th century.

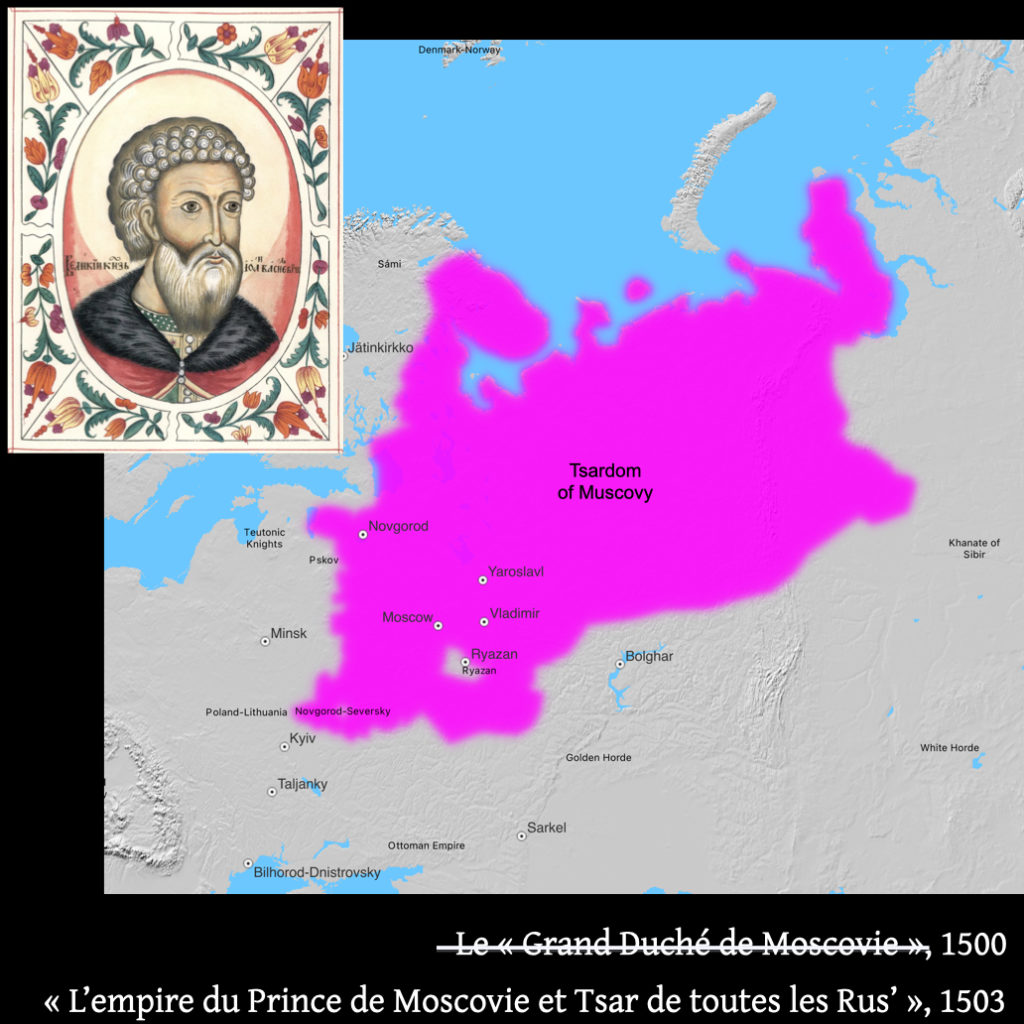

But, quite quickly, this Mongol empire crumbled because of the wars of succession. Its regions start to gain autonomy from the central power. Among the more autonomous regions, the Grand Duchy of Muscovy.

It works out pretty well for this Grand Duchy of Muscovy, as it manages to expand northward.

And, in 1503, Moscow’s Prince Ivan III begins to be called Ivan the Great, he marries the daughter of a Byzantine king and, in a Byzantine tradition, he takes the title of Tsar of Muscovy and Prince of all Rus’.

By the beginning of the 18th century, this empire extended to half of Eurasia.

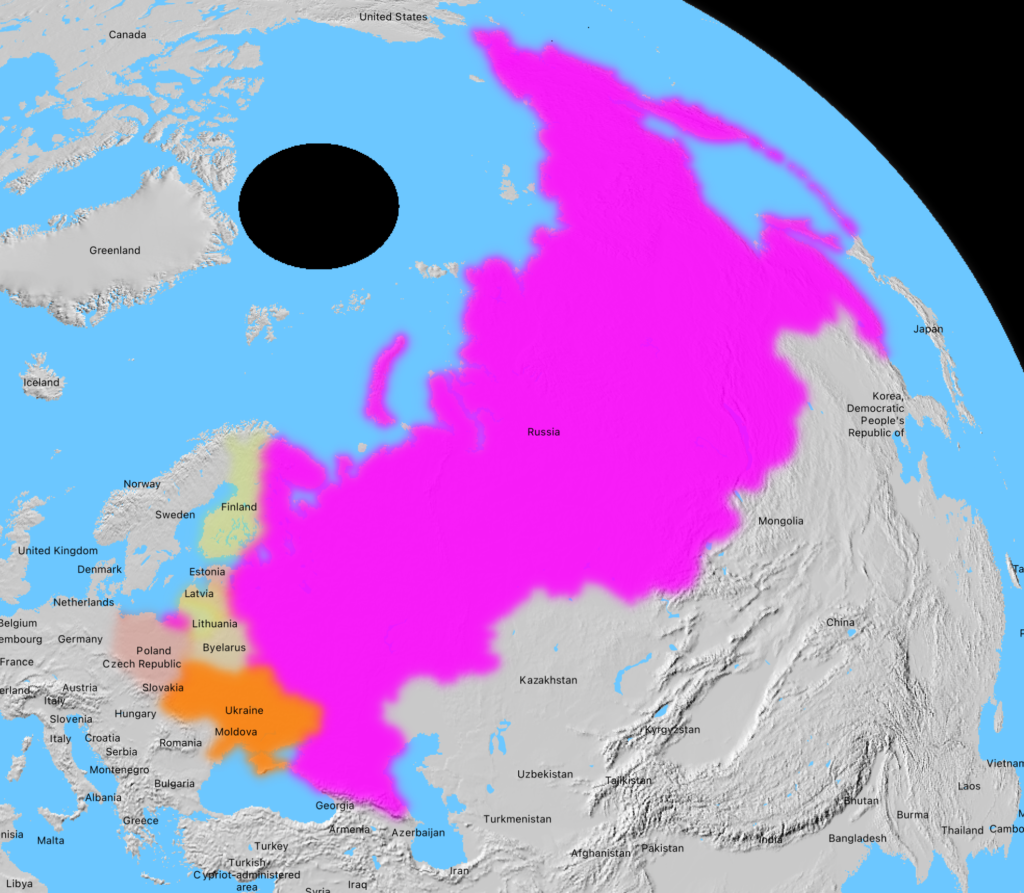

In 1721, Peter I, also called “Peter the Great”, conquers Swedish territories, he founds Saint Petersburg and he declares that his kingdom is now called the Russian Empire. He insists on this idea of Russia, since he considers that his kingdom is not an outgrowth of the Duchy of Muscovy, but the true heir of the Kyiv Rus.

Indeed, at the beginning of the 20th century, the Russian Empire had swallowed up the territories of the former Kiev Rus, but not only. It also swallowed up Poland, the Baltic countries, and Finland, among others.

Towards the end of the First World War, the Russian Empire became the Soviet Union following the Bolshevik Revolution. But some countries managed to separate from the empire, including Finland, the Baltic States, Poland and Ukraine.

Some of them were re-absorbed by the Soviet Union at the end of the Second World War.

But they become full-fledged countries again after the dismantling of the Union.

Yet today we have a bitter old man in Moscow who rambles about the Kiev Rus, the Russian Empire and the USSR, and who thinks he is Ivan the Great and Peter the Great, and because of whom almost 70,000 people have already died since February this year.

Of course, he is not acting alone: no political system can be reduced to a single person, it is always a system. Vladimir Putin is surrounded by ideologists, sycophants, and opportunists, but also by a very large part of his population which may be struggling to formulate the utopia of a future, and which therefore projects itself into another utopia: into a kind of incoherent territory made from bits of history spread over several hundreds of years and of which Putin and his followers have made a Eurasian utopia, which, they promise, will cure the Russian people of their endless nostalgia.

The Utopia of the Impossible “Here and Now”

Let us close, for now, the chapter on national mythologies that become utopias, to talk about another form of utopia, which is perhaps more fascinating. The utopia I want to talk about is the “right here”, the hic et nunc. We are, here and now, in the utopia of the place and the present moment.

For example, take this room. We are gathered here, and we feel like we share a common place. But if we really look… yes, physically, our bodies may all be here. In fact, it is certain that some of the things I have mentioned, or some of the images I have displayed on the screen, have made each of you think of something else. And no one else in the room knows what you are thinking about.

Maybe your thoughts have wandered off into a very old, very distant memory. Maybe you’ve been thinking about a problem that’s on your mind. Maybe you’re looking forward to something we don’t know about.

The idea that we are all completely present here is actually a kind of utopia.

Because we seem to be here, but we are never completely here. Our here and now is never complete, it is always scattered in many other places that are embodied by each of us. We, all of us, each and every one of us, inhabit another space that is largely inaccessible to those around us. We are never entirely present.

We inhabit in part the common physical space, and in part a plurality of invisible spaces.

Hence the fact that if we look around and say that we are all in the same space: well, that is a utopia.

Deep down, it’s always been like that. And it’s no big deal. It’s even good to remember that co-presence is a utopia, sometimes. For example, when you get lost in your thoughts, when you don’t listen for a while, and when those around you reproach you for it, you have to tell yourself that your behavior is not so strange; that maybe it’s those around you who have an overly totalitarian idea of the utopia of copresence.

What is certain, however, is that the dissolution of « here and now » has accelerated greatly.

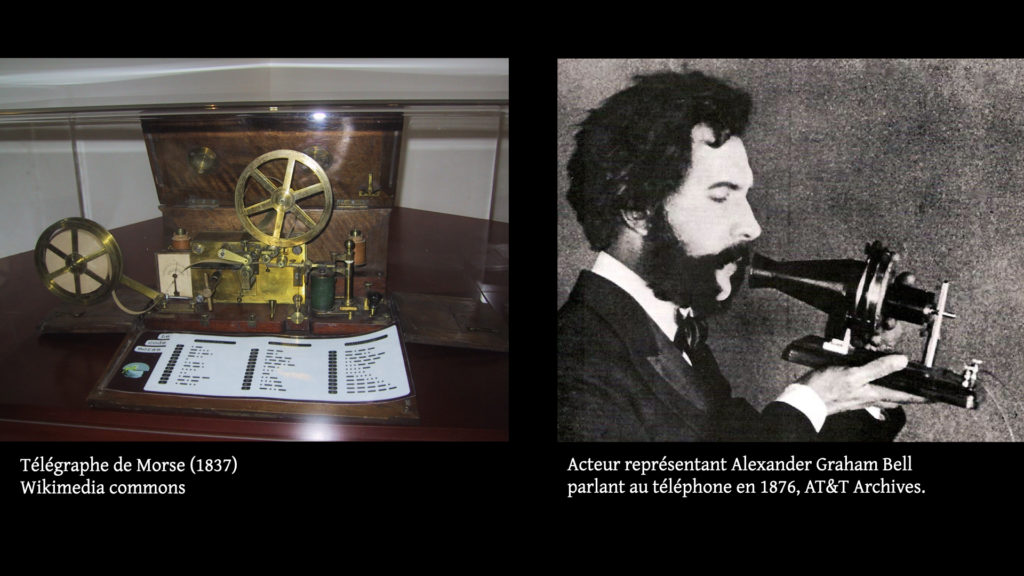

Since the 19th century, more and more powerful machines contribute to dissolve physical co-presence, by the technologies of communication. Starting with the telegraph and the telephone.

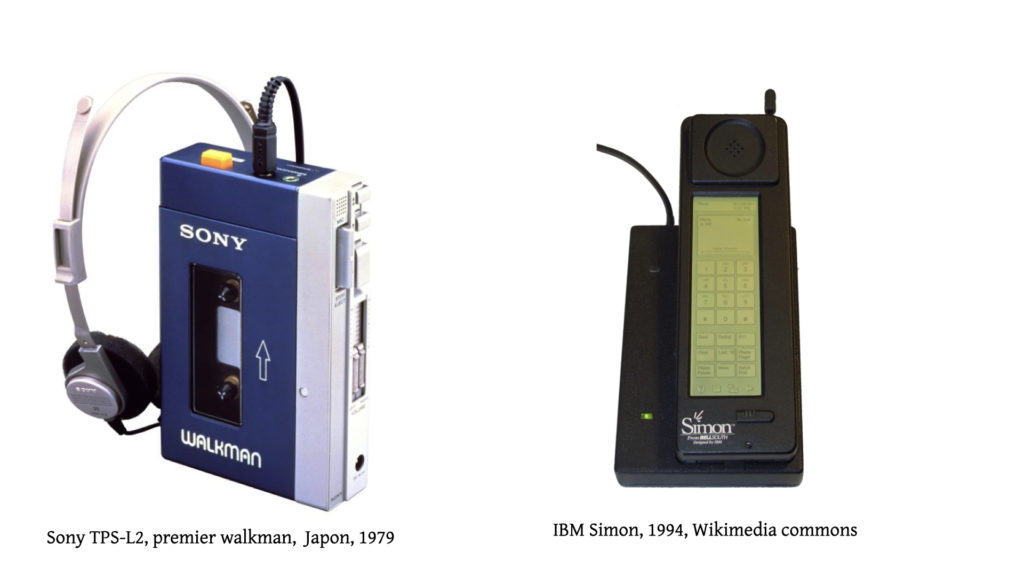

Or by devices like these.

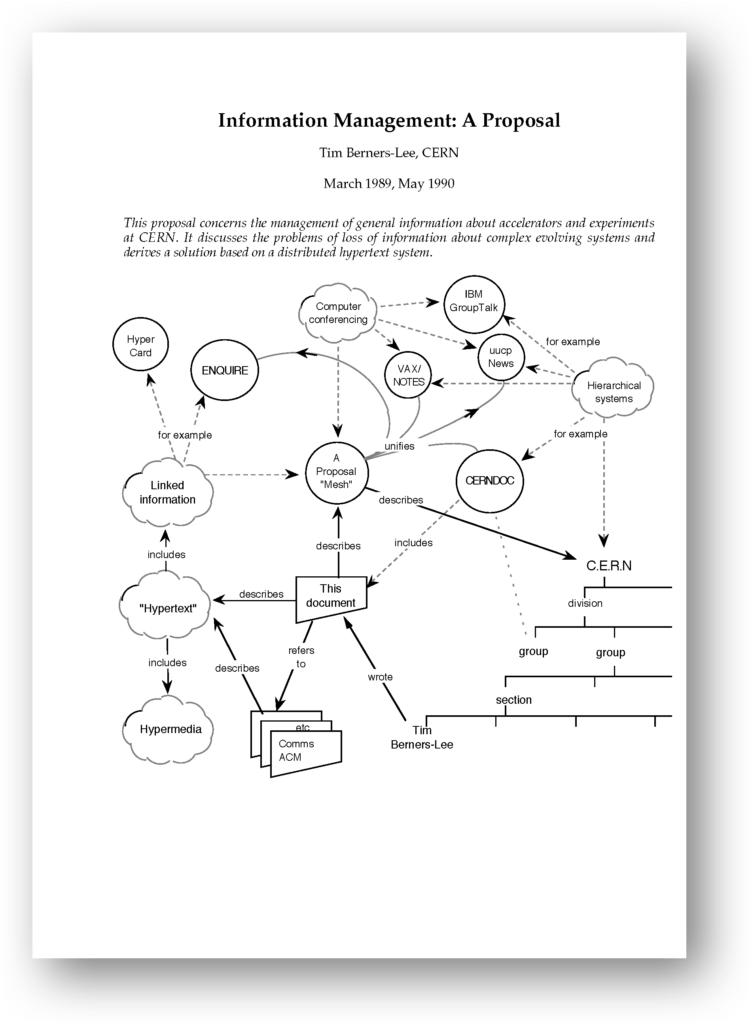

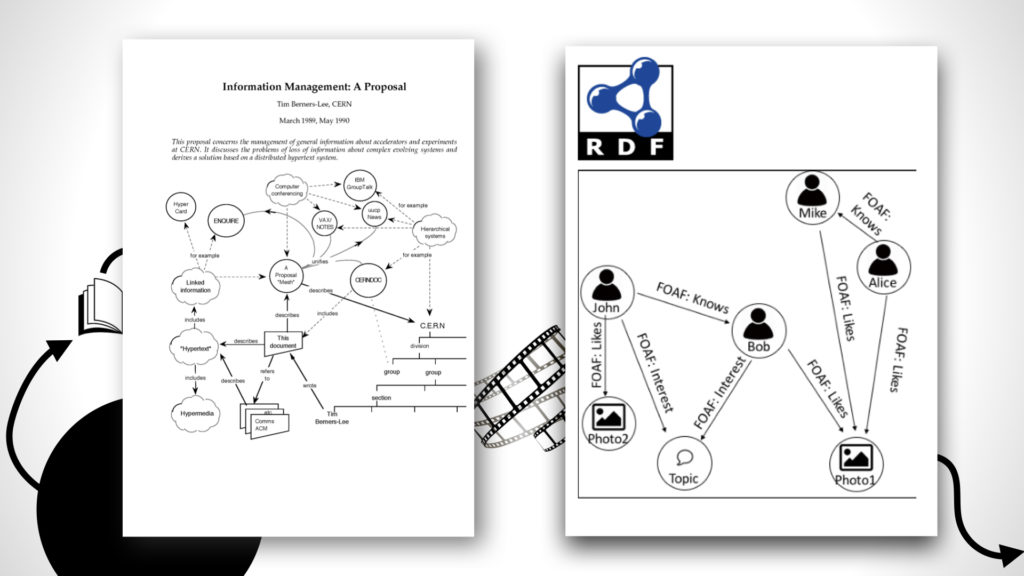

Since the 1980s, we can walk around in a personal auditory world, in an elsewhere that we carry with us. Since the 1990s, we can be contacted anywhere by a person at the other end of the world. Since the 1990s, too, we have had remote access to huge knowledge bases, thanks to an invention that was actually made in a building next to where we are, across the road: hypertext and the World Wide Web.

Now, more than 5 billion people on this planet are permanently connected to elsewhere. The consciousness of each person, here and now, is potentially increased by 5 billion other brains. And that’s not all. We now have a spectacular amount of memory. 2016: Google alone managed access to 15 exabytes of data in its various data centers. Our current digital universe is 40 zettabytes of data. By 2025, we will multiply this amount by 3. In particular, there will be a lot of small connected objects that will capture information in the world and that will feed this database. And a very large part of all this information will be accessible from anywhere and at any time.

Hypertopia

It is this enormous quantity of immediately accessible data that I call “hypertopia”. Hypertopia is not a utopia, it is not another place, nor a non-place, but it is an absolute place, a super-place, which condenses in itself all other possible places, and which swallows the world whole.

To explain myself better, I propose to look in more detail at the data that make up hypertopia.

First, the archives, encyclopedias, all the material that we deposit in the cloud servers of the Internet, for example by contributing to Wikipedia. Wikipedia, which, by the way, keeps not only the articles but the history of all changes.

Then there is everything you drop in social networks, either knowingly or unconsciously. Given that if you have installed one of its applications on your cell phone, it transmits data about you in the cloud, whether you asked for it or not. If you’re unlucky, by the way, in 10, 20 years, they’re going to pull up a Facebook post that you’d rather forget. It’s very hard to forget and reinvent yourself in this world.

Finally, if you’re a scientist, you file dozens of papers, because you know you live in a “publish or perish” world: if you don’t put lots of data in online journals, you’re going to lose your job. The result is that there is such an excess of publications that you don’t have time to read articles anymore, since you have to spend that time making a bibliography of all the ones you should read.

Georges Perec, whom I mentioned earlier, worked as a documentalist for the CNRS in the 1970s. He also mentions the problem: in ten years of his career, he went from 10 journals to summarize for his colleagues to 500 journals. If he had not been confronted with such a mass, we might have had more books by Georges Perec otherwise.

But in hypertopia, you don’t only have the past, you also have all possible futures. These futures are offered to you in the form of a system of choices so immense that it becomes impossible to choose. It affects absolutely everything, including what we call “free time” and “private life”.

Going on vacation, for instance, one is quickly distressed at the idea of not having chosen the best possible hotel among the hundreds of choices on dozens of sites. When Christopher Columbus left for the Americas, he didn’t really know where he was going. Today, you would consider yourself reckless if you didn’t compare booking.com reviews with TripAdvisor reviews.

If you use dating sites, you will wonder if the man or woman of your life is the person you see on the screen, or if you should swipe two screens further. The information is there, here and now, so you feel an oppressive sense of obligation towards yourself to see everyone before choosing.

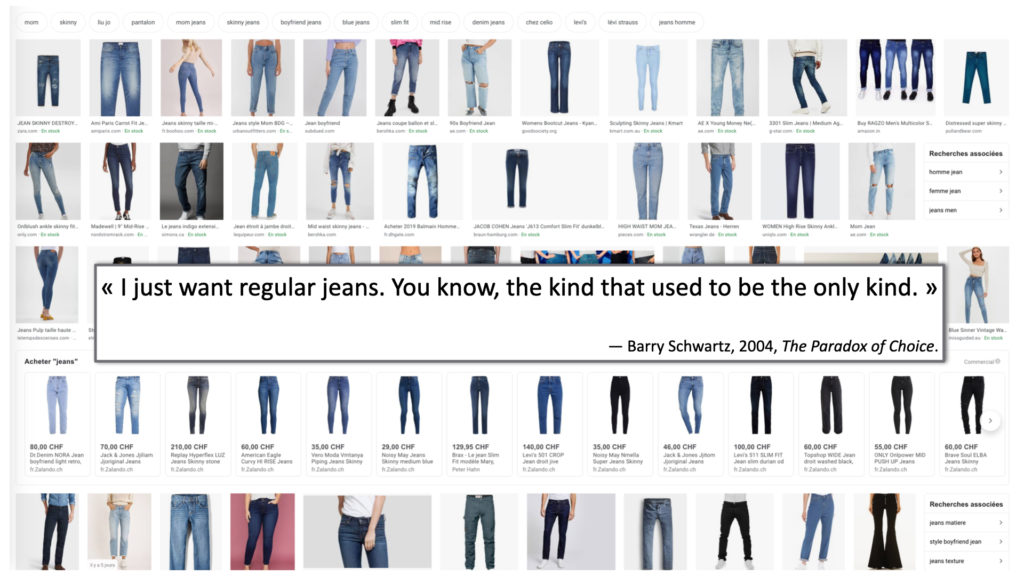

An example in the same vein is given to us by psychologist Barry Schwartz, who describes the following experiment: He wants to buy a pair of jeans.

He says, “I’m looking for a size 32 jean.”

And the salesman says to him, “But do you want it to be slim or casual, baggy or extra baggy? Stonewashed, acid washed or with holes? Do you want it buttoned or zippered? Do you want it faded or regular?

Then Barry Schwartz, completely overwhelmed by the number of choices, finally says, “I just want regular jeans. You know, the kind that used to exist when there was only one kind of jeans.”

That was 15 years ago. Now, the choice of jeans on online sales platforms is completely beyond us.

Let’s summarize: We are here, now. But that here and now is never just the here and now. Since we have all the other spaces we carry within us, and it would be enough to turn on any cell phone to be immediately invaded by all the data of the past. Or to be immediately invaded by all the proposals of possible futures. Or to be invaded by news from the other side of the planet, instantly.

If we schematize, everything that happens elsewhere, in this horizontal plane of space, does not stop flooding the present moment.

And on the vertical axis of time, the here and now is invaded from above by the possibilities of the future and from below by the memories of the past.

This presence of the elsewhere, the past and the future in the here and now has always been the case. But with contemporary information storage and telecommunication technologies, this situation has reached a new paroxysm. We are drowning in information.

Moreover, one could say that it is not these things that flood the here and now, but rather it is our here and now that absorbs them, that swallows them, becoming more and more immense, transforming space and time into an immense here, devoid of direction and saturated with itself. This is what I call hypertopia.

As we are at CERN, there is, of course, an image, a physical metaphor that immediately comes to mind: it is the metaphor of a black hole: a star collapsed on itself. It is a place whose mass and density are such that even light can no longer escape.

A black hole is also called a singularity: it is the convergence of matter in a single point.

Hypertopia is the convergence of ideas, imaginary, information in a single point.

Hypertopia is when the mass of data available here and now becomes so great that it makes us unable to project ourselves outside the here and now.

Hypertopia is when the light of our imagination is no longer able to illuminate the future; it is when our imagination becomes trapped in the past and the enumeration of possible choices.

The question is: how to get out of the hypertopic black hole we are falling into?

On an individual scale, how can we imagine a new identity, a new form of existence when everything refers us to what we already are and which is overloaded? With hard drives full of photographs, our administrative trace, our interactions on social networks, our publications, which we may be asked to justify 20 years later?

How can we imagine utopias when we know all the possible dystopias and utopias? When everything seems to have been tested without success?

How can we imagine the future of a country when it is haunted by a history that is not even its own, and which has become clumped together in an inextricable body of incoherent fantasies?

How to re-imagine the future? How to re-imagine the elsewhere?

Out of Hypertopia

The Easy Way Out: Becoming Followers, or the Temptation of the Heroic Figure

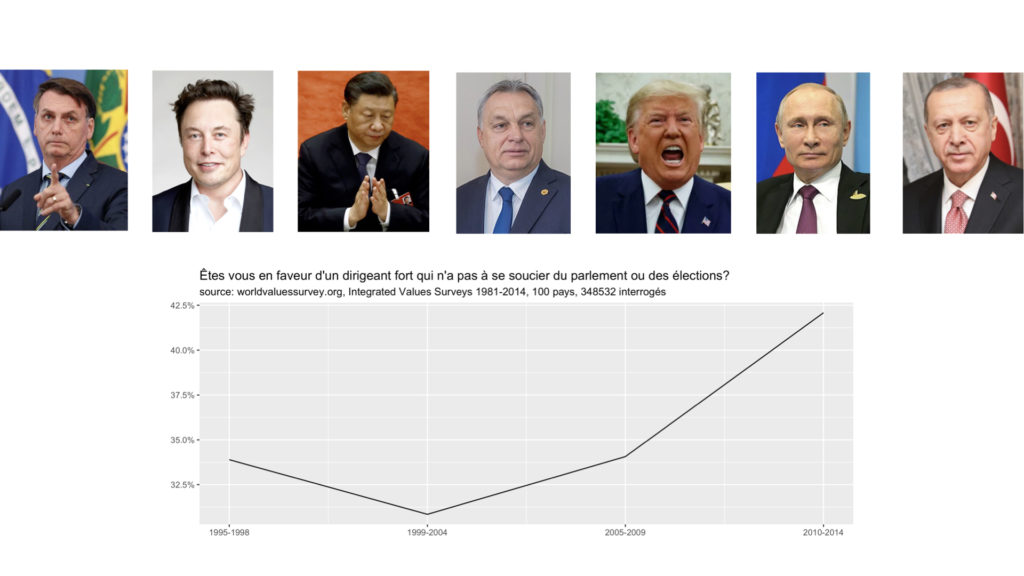

One of the solutions, which is still not out of fashion, is that of the strong leader. Someone who is able to make choices for us, to pull us out of the black hole of indecision and to carry us into the future.

This can be seen, for example, in the World Values Survey, conducted between 1998 and 2014 in some sixty countries on all continents. This study interviewed between 1000 and 3000 people per country. There was a disturbing evolution:

In 1998, only 30% of respondents were in favor of a “strong leader who does not have to worry about parliament or elections.” That number rose to over 40% in 2014.

Earlier in the presentation, I talked about nostalgia and the false remedy of utopian territorial rootedness. I’ll add that I think hypertopia also contributes to this trend. Since when our here is saturated, when our identity dissolves, when we are overwhelmed to the point of being unable to form a clear picture of the past, or to project ourselves into the future beyond the mass of data that is thrust upon us… well, a simple discourse, a clear readability of power may seem like a solution.

The Data Way Out: the Faith in Statistics and Algorithms

The other possibility, which is more inclined in technocratic democracies, is statistics and algorithms.

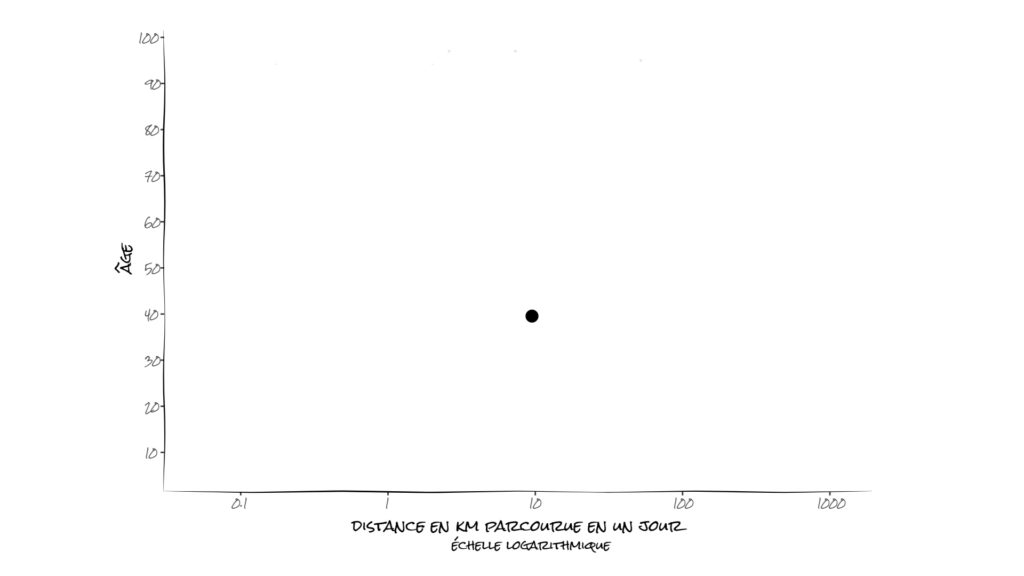

To demonstrate: imagine a simple statistic. We have 2 axes: space and time.

Space, horizontal axis: number of km you drive per day.

Time, on the vertical axis: your age.

With this system, we can conduct a survey by asking each of you how old you are and how many kilometers you traveled yesterday. Let’s say you are 40 years old and yesterday you walked 10 kilometers. We can represent you as a point in this coordinate system.

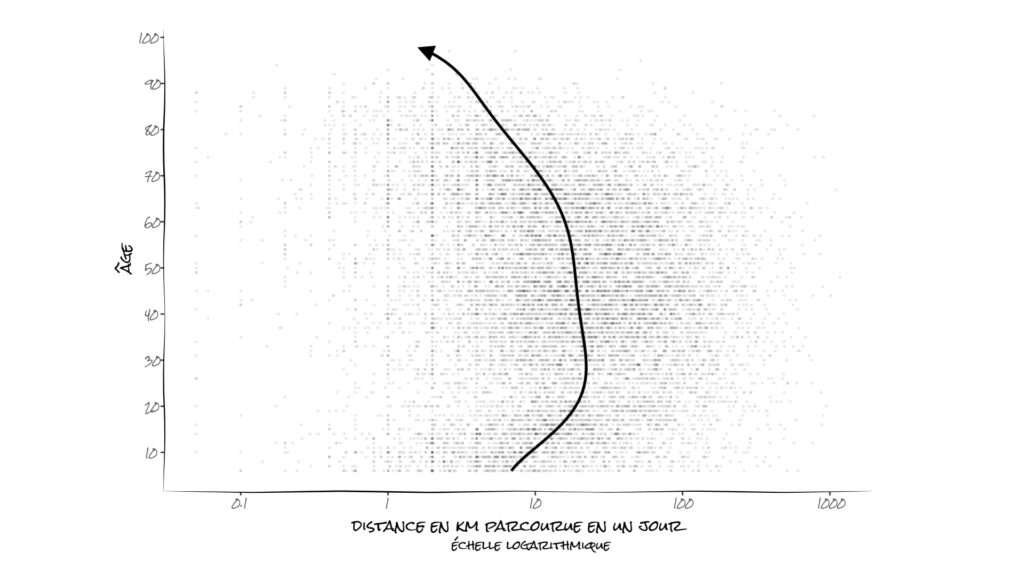

Then, if you do that with 20,000 people, it gives you a scatter plot.

Once you have a scatter plot, you can do a statistical model. For instance, a 7th-degree polynomial regression, whose curve gives you the average trend.

After that, you can adopt a very standard assumption: that the behavior of today’s young people will resemble that of their elders, when they themselves get older. And when you adopt that assumption, your regression curve becomes a prediction.

You say “on average” a person moves more and more until the age of 20…, then that person will move fewer and fewer miles per day until retirement age. From that point on, your mobility will decrease much more drastically until you stop in your grave for good.

So, so far, it’s a prediction, but the problem with statistical predictions is that they easily become self-fulfilling prophecies, especially when they are seized upon by advertisers.

Looking at a statistic like this, the marketing department of a social network knows, for example, to show ads for travel destinations and cars to the under-25s, since they are in the midst of their mobility boom. For the over-60s, on the other hand, the advertiser thinks it’s better to show ads for gardening tools.

It’s caricatured, of course, but you get the idea. This is what is called, in cybernetic language, a positive feedback loop. Or a self-reinforcing phenomenon, since, through the effect of publicity, the central tendency will be reinforced. Because you will always be shown ads that correspond to the average desire of your age group, or more generally of your social group. And if you follow the advertising injunction, well, you change your behavior, you move closer to the regression line, and so you further reinforce the average trend it represents.

Which means that eventually everyone, all the data points, will end up clustered around the center line. And there will be only one life course for all the individuals.

Here, it is, again, a caricature with only one variable, which is the number of kilometers traveled per day. But you should know that every day we deliver petabytes of information to social networks, which makes their statistical predictions more and more detailed. Their data has thousands of dimensions, where the courses of our lives are inscribed, and where average trends emerge. In each dimension, the advertisement proposes the predictable, and therefore normal, continuation of our course, and in doing so, we are led to follow the general trend.

So we no longer have a hypertopic black hole, but a black line in space-time. Like a flycatcher to which we will all end up sticking. This is at least what is likely to happen to us if we rely on statistics and search engine algorithms to try to extract us from hypertopia.

The Complex Way Out: Towards an Existential Epistemology of the Itinerary

So how do we really get out of the black hole of hypertopia?

- A first proposal would be to avoid social networks and advertisements.

- It would also be to avoid totalizing utopias. To avoid the great historical narratives projected into utopian territories.

- On the contrary, I think we should trust chance, the uncontrolled part of reality.

- Let us follow the tracks, let us follow our intuitions. Each object, be it a book, a film, a city, a tree… each object refers to many other objects. Some tracks leave us indifferent; we don’t know why. Others will fascinate us; we also rarely know why. But we never have to justify our fascinations. We don’t have to justify the inspiration we get from the objects we meet on our way.

Perhaps that is exactly what this inspired journey through a reticular world is all about, the essence of the founding project of the Internet and hypertext. It may also be the essence of the semantic web that is being developed today.

- Never apologize for the bifurcation of our intellectual or life paths.

- Do not worry about exhaustiveness and omniscience, even if you are a scientist. What legitimizes your speech, your thoughts, what gives you the right to speak in the public space, is not the fact of knowing everything and it is not the fact of being the expert of a narrow field. What gives each of us the right to speak out in the scientific and political arena is the specificity of our journey of knowledge, the length of our path, and the passion we have invested in each of its stages.

This is how we trace a relevant path, a path that makes sense for each of us and also for others. For, and this is my final point, we must trust that many others will follow their own path of knowledge and passion, just as we do.

Because what happens when no one claims to have the big picture and everyone follows their own thought processes. What happens, though, is that these routes intersect. These threads intersect. Our thoughts meet. And by crossing each other, they form a fabric.

This fabric, one can imagine it floating in the ocean of unknown realities. This fabric, for me, is an image of the consciousness of humanity. Not only an image but an epistemological posture, an ethic of science that I would like to propose to you to get out of past utopias as well as hypertopia.