Jean-Jacques Rousseau would have been 300 years old today. He was already 53 in October 1765 when he left the waves of the Lake Bienne, heart-sick, expelled from the Island of St. Peter upon the order of the bailiff of Nidau. His expulsion is almost like a self-fulfilling prophecy. Fifteen years ago, in his Discourse on the Arts and Sciences, he praised the dawn of men, the “early times” which he described as “beautiful coast, adorned only by the hands of nature; towards which our eyes are constantly turned, and which we see receding with regret.”

He will never know exactly who hatched the expulsion order, or why. Even today, long time after his death, the political confrontations around his character remain mysterious at times. In the little Swiss town of Yverdon, for instance, right wing liberals went to great lengths to prevent his work from being commemorated in their streets. In 1912 already, the controversy raged around the bicentenary of the philosopher. The French nationalist Maurice Barres then denounced Rousseau as an “apostle of all anarchies”.

Rousseau, in his lifetime, perceived only the effect of the “dark construction” (édifice des ténèbres) whose paranoid shadow follows him in any shelter. The expulsion from Saint-Pierre is not his first, but this one is different: it marks the end of two “the happiest months of his life,” spent alone, feeling his “own existence without bothering to think”, as he wrote in his Confessions and his Reveries:

“The various soils of which the island, though small, was composed, offered me a sufficient variety of plants to study and to rejoice seeing for the rest of my life. “‘When evening approached, I walked down the peaks of the island and I was happy to sit by the lake in a hidden sanctuary; there the sound of the waves and the agitation of the water layed my senses to rest, chasing all other agitations from my soul, plunged them into a delicious reverie; and the night often surprised me without me noticing.”

He shall find similar conditions only in the grave, in which he’ll be laid on a small island, in the lake of René de Girardin, in Ermenonville near Paris, in the shade of poplar trees. Soon, however, some murderers of the century also came to commune with themselves in this fresh shade: Marat, a native of Reunion Island; Bonaparte, who shall rule, one day, on the parody of an empire – Elba – before his final fade-out on the island of St. Helena. Four years before the birth of Bonaparte in Corsica, the island had asked Rousseau to write its constitution. But the same year Bonaparte was born, the island lost its status of autonomous republic. Its constitution, as Rousseau had written on St. Peter, never enters into force.

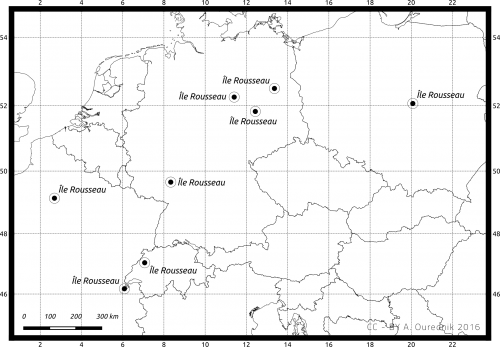

Shortly after the philosopher’s death in 1778, however, ten islands similar to his last refuge in Ermenonville, and bearing Rousseau’s name, spread in Europe: the “Rousseau Island” in Geneva, in Worlitz (Saxony-Anhalt), in Berlin’s Tiergarten, in Arcadia Park near Nieborów (Poland).

The peculiarity of the “Rousseau Islands” is that none is far from shore. Only the water of a lake, or a pond, isolates them from the surrounding continent, and from the men who inhabit it. Sometimes there is simply no water, only poplars around a mound of earth, like the “Tomb of J. J. Francois Rousseau” erected by Maurice de Lacy in Neuwaldegg near Vienna. Metaphorically speaking, these islands are perhaps all replicas of this delicate solitude, where man, confronted to no-one, limited only to the capacity of his body, and with nature as his only entourage, can only be “good”, whoever he is. It is probably easier to be a saint, when isolated from the world and from the sounds of the city, where one sees only “walls, and street crimes”, as Rousseau did. And no doubt more obvious to be “just” when unexposed to friction with otherness – that otherness who can bring forward the ugly creature living in the depth of anyone, but who everybody denies being…

Most Rousseau Islands shall suffer flooding. The one in Geneva is hosting a pub. That of St. Peter ceases to be an island in 1878, becoming a peninsula following the correction of the Jura waters. Rousseau’s body is not to be found on any of them. He was transferred to the Pantheon in October 1794, upon the decision of the Thermidor Convention, a few months after the beheading of Robespierre, who, too, had communed with himself, one day, on the Island in Ermenonville. Cities seem to possess a certain power to absorb their opponents in their necropoleis.

The ephemeral fate of the islands, meanwhile, testifies of a nature very indifferent to the idyllic image the philosopher draws of her. A nature who cares little about its own “idyllic” role and status, in short, but a fragile idyll nevertheless, if the word “idyll” is to designate an environment welcoming to the human species and nature.

As for Rousseau, finally, the most fitting tribute to his life may be found in the Ballad of the Adventurers by Bertold Brecht, here translated by John Willett, and sung by David Bowie:

Sickened by sun, with rainstorms lashing him rotten

A looted wreath crowning his tangled hair

Every moment of his youth apart from its dream was forgotten

Gone the roof overhead, but the sky was always there

Oh you, who are flung out, alike from heaven and from Hades

You murderers who’ve been so bitterly repaid

Why did you part from the mothers who nursed you as babies

It was peaceful and you slept and there you stayed

Still he explores and rakes the absinthe green oceans

Though his mother has given him up for lost

Grinning and cursing with a few odd tears of contrition

Always in search of that land where life seems best

Loafing through hells and flocked through paradises

Calm and grinning, with a vanishing face

At times he still dreams of a small field he recognises

With a blue sky overhead and nothing else

Bertold Brecht, transl. from German by John Willett, The Ballad of the Adventurers